Hygienic safety of alcohol-based hand disinfectants and skin antiseptics

Katrin Steinhauer 1Bernhard Meyer 2

Christiane Ostermeyer 3

Hans-Joachim Rödger 4

Matthias Hintzpeter 5

1 Schülke & Mayr GmbH, Research & Development, Norderstedt, Germany

2 Ecolab Deutschland GmbH, Research & Development, Düsseldorf, Germany

3 Bode Chemie GmbH, Microbiology, Hamburg, Germany

4 Lysoform Dr. Hans Rosemann GmbH, Berlin, Germany

5 B. Braun Melsungen AG, Regulatory Affairs, Melsungen, Germany

Abstract

Purpose: The aim of this study was to evaluate the overall risk of hand disinfectants and skin antiseptics to become contaminated with bacterial spores throughout the production process and the subsequent in-use period, hence posing a public health risk.

Methods: Microbiological assessment of primary packaging material was carried out and long-term survival of bacterial spores in alcohol was assessed using sporulated B. subtilis ATCC 6633 as a standard.

In-use contamination of alcohol-based formulations was tested by repeated use over 12 months under practical conditions and microbiological and physico-chemical data were determined.

Results: Among 625 containers analyzed, 542 did not yield any microbial growth. Median colony count for aerobic spore-forming bacteria was 0.2 cfu/10 ml container content. No anaerobic spore-forming bacteria were detected. Additionally, long-term survival of bacterial spores in aliphatic C2–C3 alcohols revealed 1-propanol to reduce the number of spores most effectively, with 2-propanol and ethanol having a somewhat less pronounced impact. In-use tests did not detect any microbial contamination or change in the physicochemical properties of the tested products over 12 months.

Conclusions: Our data reveals that state-of-the-art production processes of alcohol-based hand rubs and antiseptics can be regarded safe. Primary packaging material and use were not found to pose a significant contamination risk as far as bacterial spores are concerned. Based on the data from this study, a microbial limit of <1 cfu/10 ml can be suggested as a quality-control threshold for finished goods to ensure high quality and safe products.

Keywords

hand disinfectants, skin antiseptics, spores, hygienic safety, contamination, alcohol

Introduction

Application of alcohol-based hand rubs in hygienic and surgical hand disinfection is of great importance and highly recommended to prevent healthcare-associated infections [23]. Alcohol-based products are also state of the art in skin antisepsis [4]. Although skin sterility cannot be achieved using hand disinfectants and skin antiseptics [18], [19], [22], the risk of healthcare-associated infections is reduced significantly [23].

However, the alcohols commonly used as disinfectants and antiseptics are not regarded as sporicidal at contact times relevant for disinfection and antisepsis [1].

Although the majority of aerobic spore-forming species are considered to have little or no pathogenic potential, rare but severe infections have been associated with Bacillus spp., especially in immunocompromised patients [3], [11], [16].

The US CDC reported spread of Bacillus spp. due to contaminated alcohol prep pads. Non-sterile alcohol prep pads containing 70% 2-propanol were found to be contaminated with B. cereus and other Bacillus spp. [5]. Accordingly, Berger has described a case of pseudo-bacteremia due to contaminated alcohol swabs, which was clearly associated with highly contaminated cotton swabs [2]. Thus, careful attention must be paid to auxiliary material with regard to its microbiological status. This also applies to primary packaging material. A careful evaluation of the contamination risk posed by each material coming into contact with the alcohol-based product and suitable procedures including sterile filtration is essential to control this risk.

The aim of the present study was therefore to evaluate the overall risk of hand disinfectants and skin antiseptics to become contaminated with bacterial spores throughout the production process and the subsequent in-use period, hence posing a public health risk.

Methods

Bacterial strains and standard growth conditions

Sporulated B. subtilis ATCC 6633 was used as a standard to test the alcohol tolerance of bacterial spores over extended periods. B. subtilis spore suspensions (108 cfu/ml; L+S AG, Bad Bocklet, Germany) were stored in aqua ad iniectabilia. According to the manufacturer, spore suspensions were heated for 10 min at 95°C. The spore suspension titre was determined and adjusted if necessary to yield 107 cfu/ml. Spore suspensions were checked for sporulation and titres using bright-field microscopy and a Helber bacteria counting chamber.

For microbiological assessment of primary packaging material, 0.45 µm cellulose-acetate membrane filters (Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany) were incubated on tryptone soya agar (TSA) Schaedler blood agar (BD Diagnostic Systems, Heidelberg, Germany) or Columbia agar (Oxoid, Wesel, Germany). For TSA cultivation, filters were incubated under aerobic conditions at 35±2°C for 48 h. For cultivation on Schaedler blood or on Columbia agar, filters were incubated anaerobically for 72 h at 35±2°C. All colonies detected under anaerobic conditions on Schaedler blood or Columbia agar were transferred to TSA and cultivated under aerobic conditions for 72 h at 35±2°C.

Staining procedures and microscopy

Sporulation was monitored using bright-field microscopy. 5 µl of each spore suspension was heat-fixed on a glass slide, stained with 5% malachite green aqueous solution and steamed for 20 s. The slides were rinsed with water and counterstained for 1 min using 2.5% eosin G aqueous solution.

Assessment of primary packaging material for bacterial spores

Microbiological assessment of primary packaging material was carried out using five different types of containers and their respective caps typically used: 50-ml plastic pocket bottles (high-density polyethylene; HDPE; Kaller Kunstofftechnik, Germany) with polypropylene (PP) caps (hinged breech block Euro; Zeller Plastik, Zell, Germany); 100-ml plastic bottles (HDPE; Rebhan GmbH, Stockheim, Germany) with PP caps (Zeller Plastik); 250-ml round plastic bottles (HDPE, Promens Packaging GmbH, Witzenhausen, Germany) with Fine Mist Sprayer caps (Mistette MK II; MeadWestvaco Calmar GmbH, Germany); 500-ml plastic bottles (HDPE; Sauer Polymertechnik, Germany) with PP caps (Krallmann Kunststoffverarbeitung, Germany); and 5-l canisters (HDPE; E+E Verpackungstechnik, Germany) with HDPE caps (GFV Verschlusstechnik, Germany). These materials were manufactured under current state of the art conditions, i.e. in a visibly clean environment, but without specific air filtration. The sample size (each 125 items) was calculated according to DIN ISO 2859-1, general inspection level I, sample size code letter K, single sampling plan for normal inspection [12]. The primary packaging material was selected at random and taken from production sites under hygienic conditions. Before microbiological assessment caps were added to their respective containers, which were disinfected from the outside (excluding caps) using an alcohol-based disinfectant [25 g ethanol (94%) and 35 g 1-propanol]. The containers were opened in a laminar flow cabinet and filled to 1/5 of the total volume with sterile filtered ethanol 70% (v/v) for elution of bacterial spores. Repositories were closed with corresponding caps and shaken thoroughly for 60 s. Elution liquid was divided into two equal volumes and membrane-filtered using a 0.45-µm cellulose acetate membrane. Each filter was rinsed with 100 ml tryptone-NaCl solution (TSL). One filter was incubated on TSA, and the other under anaerobic conditions on Schaedler blood or Columbia agar, as described above.

Sporulated B. subtilis ATCC 6633 was used for validation of growth of aerobic spore-forming bacteria. One container was filled to 1/5 total volume with 70% ethanol (v/v), which was used as an elution solution. A second container was filled with TSL, which was used as a rinsing solution. Both containers were closed with caps and agitated for 1 min. Half of the rinsing solution and half the elution solution were membrane-filtered using a 0.45-µm cellulose acetate membrane. Each filter was rinsed with 100 ml TSL, to which 1 ml B. subtilis ATCC 6633 (titre >101 to <102 cfu/ml) was added. Membrane filters were incubated on TSA for 72 h at 35±2°C and growth of B. subtilis spores was verified. Growth of anaerobic spore-forming bacteria was validated using Clostridium sporogenes ATCC 19404 as a standard for validation of growth of anaerobic spore-forming bacteria on Schaedler blood or Columbia agar, which was carried out under anaerobic conditions, as described above.

All colonies detected on TSA were multiplied by 2, as only half of the elution volume was used for membrane filtration and subsequent cultivation on TSA. Numbers are reported as aerobic and facultative anaerobic spore-forming bacteria. All colonies detected on Schaedler blood agar, which did not grow on TSA under aerobic conditions, were similarly multiplied by 2 and numbers were reported as strictly anaerobic spore-forming bacteria.

Acceptance criteria for validation of growth were as follows: 0.5–2 = initial bacterial count/recovered bacterial count.

Long-term survival of bacterial spores in C2–C3 aliphatic alcohols

To assess long-term survival of bacterial spores in different alcohols, freshly distilled ethanol was mixed with sterile deionised water in sterile glass bottles to give 95, 80, 60, or 40% (v/v) in 50 ml final volume. Freshly distilled 1-propanol or 2-propanol was mixed with sterile deionised water in sterile glass bottles to give 70, 50, 30, or 10% (v/v) in 50 ml final volume.

To test the extended alcohol tolerance, 50 µl B. subtilis spore suspension (107 cfu/ml) was mixed with 50 ml ethanol, 1-propanol, or 2-propanol. 110 sterile glass beads (Ø 3 mm; Soda-Kalkglas; Th. Geyer, Germany) were added to each glass container to avoid adhering and clumping of the spores. Sampling was carried out once or twice weekly. Samples were mixed thoroughly for 30 s and 1-ml samples were taken immediately for determination of log Na (Na = cfu/ml sample), mixed thoroughly with 9 ml germination medium in the presence or absence of lysozyme (25 µg/ml) and incubated for 15 min at 30±2°C to allow spore germination, as described previously [6], [17]. Lysozyme did not affect cfu detection; therefore, cfu were determined for each sample by serial dilutions using the germination medium lacking lysozyme and subsequent cultivation on TSA, as described above.

Non-toxicity of the germination medium was verified by validation experiments according to EN 13704 [7].

All experiments were reproduced three times in and results are given as mean values. Error bars represent standard deviations. Data are reported as logarithmic reduction factors RF = lg N0 – lg Na, where N0 is cfu/ml of control (water) and Na is cfu/ml in sample after exposure to the respective alcohol at indicated contact time.

In-use contamination and stability of alcohol-based formulations

An in-use test of alcohol-based formulations was carried out with a typical alcohol-based hand disinfectant [Formulation A; 73.4% (w/w) ethanol, 10% (w/w) 2-propanol] and alcohol-based skin disinfectant [Formulation B; 74.1% (w/w) ethanol, 10% (w/w) 2-propanol]. Both disinfectants were challenged by repeated use over a period of 12 months under practical conditions. Each sample underwent ~150 simulations. The test took place under open conditions in a conventional laboratory for application tests without air conditioning or filtering. The room temperature was 18–32°C.

Microbiological and physico-chemical data were determined. At the end of the test, a sealed reference sample of each product, stored in parallel to the test samples, was analysed for the same quality parameters.

A 1-l bottle was used for the tested hand disinfectant, and normal use was simulated by pouring 5 ml product via the snap-cap closure of the bottle three times a week over a period of 12 months. The skin disinfectant was packed in 250-ml bottles with a spray pump. Normal use was simulated by a threefold activation of the pump equalling ~1 ml over a period of 12 months, three times weekly.

For the microbiological assessment, 100-ml samples of the respective disinfectant were used and processed according to European Pharmacopoeia 2.6.12 [8].

Active substances were assayed by head-space gas chromatographic methods. Tests for relative density were carried out according to European Pharmacopoeia 2.2.5 [8], using an oscillating transducer density meter.

Results

Bacterial spores on primary packaging material

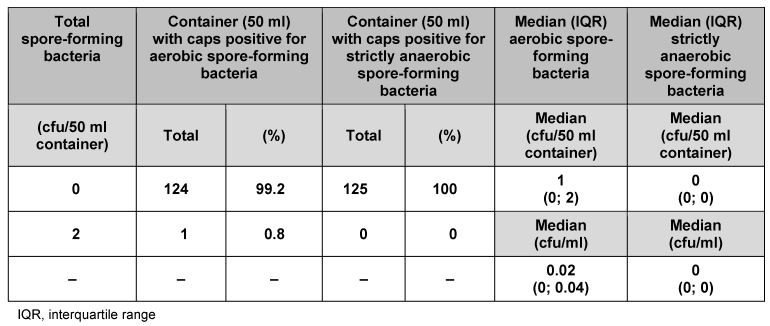

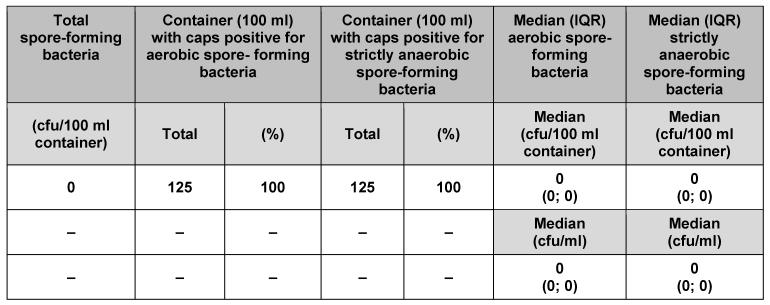

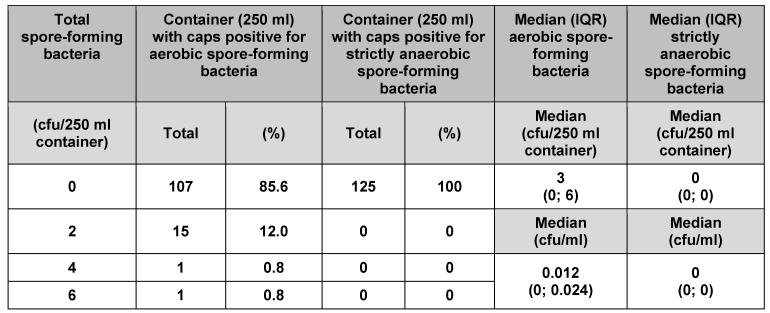

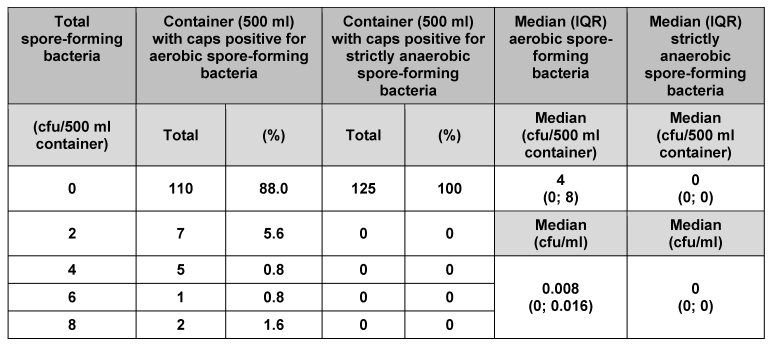

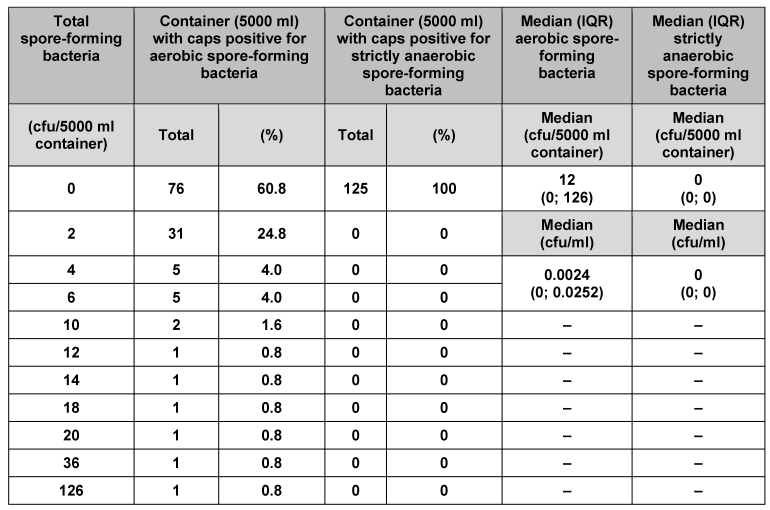

We analysed 125 individual containers (50 ml) and their corresponding caps (Table 1 [Tab. 1]). No strictly anaerobic spore-forming bacteria were found. In 124 of the containers and their corresponding caps (99.2%), no aerobic spore-forming bacteria were detected. Only one of the containers (0.8%) had 2 cfu aerobic spore-forming bacteria. Median counts for 50 ml primary packaging material were 1 cfu/container and 0.02 cfu/ml for aerobic spore-forming bacteria, and 0 cfu/container and 0 cfu/ml for strictly anaerobic spore-forming bacteria. Analysis of the other pack sizes (100, 250, 500 and 5000 ml) indicated consistently low bacterial counts (Table 2 [Tab. 2], Table 3 [Tab. 3], Table 4 [Tab. 4], Table 5 [Tab. 5]). The respective median values of all investigated pack sizes as given in Tables 1–5 revealed a maximum of 0.02 cfu/ml for contamination of the samples with bacterial spores.

Table 1: Assessment of primary packaging material for bacterial spores

Table 2: Assessment of primary packaging material (100 ml container) for bacterial spores

Table 3: Assessment of primary packaging material (250 ml container) for bacterial spores

Table 4: Assessment of primary packaging material (500 ml container) for bacterial spores

Table 5: Assessment of primary packaging material (5,000 ml container) for bacterial spores

Long-term survival of B. subtilis spores in aliphatic C2–C3 alcohols

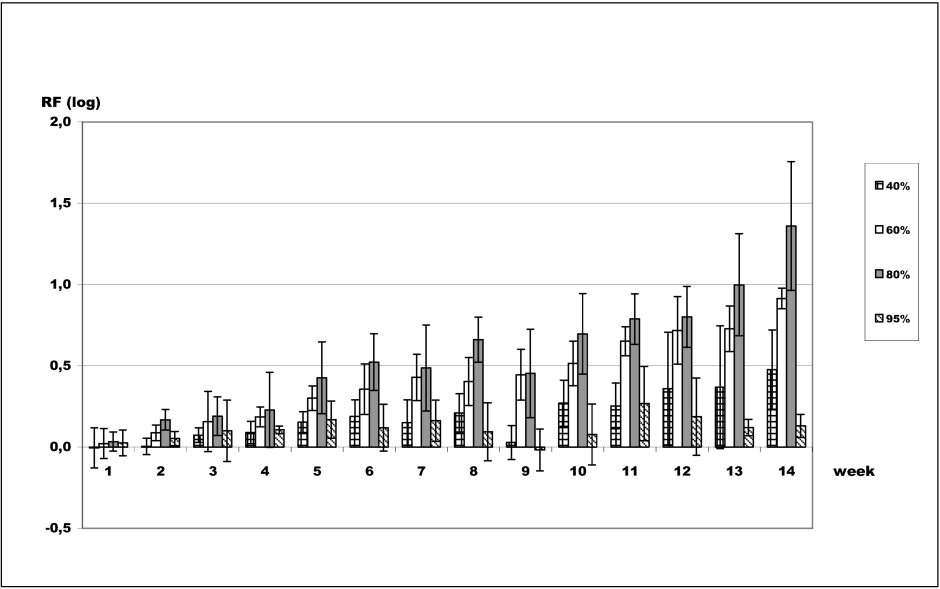

The efficacy of aliphatic C2–C3 alcohols against B. subtilis spores was investigated over the long term. Long-term survival rates of B. subtilis spores were determined using ethanol, 1-propanol, and 2-propanol at concentrations typically found in disinfectants and antiseptics. Figure 1 [Fig. 1] shows long-term survival of B. subtilis spores in 40–95% ethanol. Concentrations of 60% and 80% ethanol had the greatest impact on survival of B. subtilis spores over the long term when compared with the water control. Average logarithmic reductions of 0.43 for 60% (v/v) and 0.49 for 80% (v/v) ethanol were found after 7 weeks contact time, increasing to 0.92 log for 60% and 1.36 log for 80% ethanol at 14 weeks contact time. Concentrations of 40% and 95% were found to be less effective. Viability of bacterial spores was only negligibly affected at 7 weeks, which was demonstrated by the minimal variation in the average logarithmic reduction factors [0.15 log (40%) and 0.16 log (95%)]. However, at week 14, viability decreased slightly, and an average reduction of 0.48 log was determined for 40% ethanol, whereas average reduction for 95% ethanol remained unchanged (0.13 log).

Figure 1: Long-term survival of B. subtilis spores in ethanol. Assessment of viability of B. subtilis spores after exposure to ethanol. Data are reported as logarithmic reduction factors RF = lg N0 – lg Na, where N0 is cfu/ml of control (water) and Na is cfu/ml in sample after exposure to the respective ethanol concentration at indicated contact times. The experiments were reproduced three times and data are given as mean values. Error bars represent standard deviations.

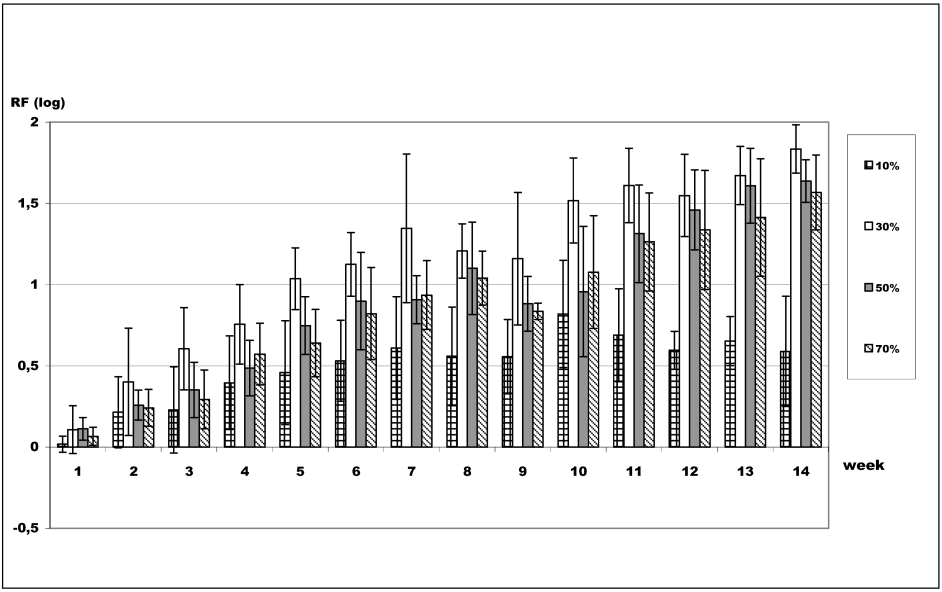

Figure 2 [Fig. 2] indicates that long-term survival of B. subtilis spores in 1-propanol was most affected at concentrations of 30 and 50%, resulting in an average reduction of 1.35 log for 30% 1-propanol and 0.91 log for 50% 1-propanol after 7 weeks contact time. For 70% 1-propanol, an average reduction of 0.94 log was detected after 7 weeks contact time. After 14 weeks, the average reduction increased to 1.54 log. Ten percent 1-propanol was the least effective concentration over the long term, resulting in a reduction of 0.61 log after 7 weeks, which remained almost unchanged after 14 weeks (0.59 log).

Figure 2: Long-term survival of B. subtilis spores in 1-propanol. Assessment of viability of B. subtilis spores after exposure to 1-propanol. Data are reported as logarithmic reduction factors RF = lg N0 – lg Na, where N0 is cfu/ml of control (water) and Na is cfu/ml in sample after exposure to the respective 1-propanol concentration at indicated contact times. The experiments were reproduced three times and data are given as mean values. Error bars represent standard deviations.

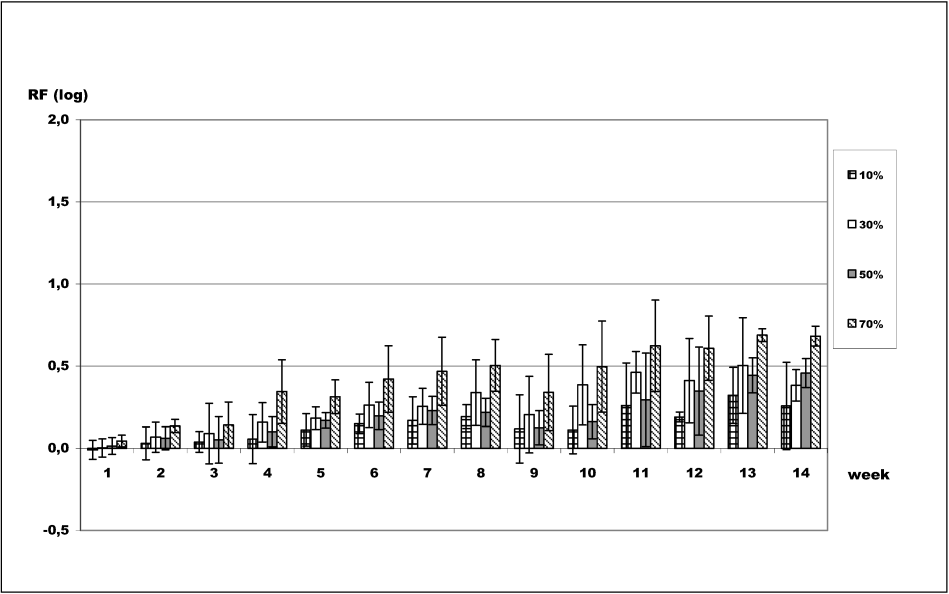

Figure 3 [Fig. 3] shows the impact of 2-propanol on long-term survival of B. subtilis spores. For 2-propanol, 70% was the most effective concentration, and 10% was the least effective. After 7 weeks contact time, average logarithmic reductions were 0.17 log (10%), 0.26 log (30%), 0.23 log (50%), and 0.31 log (70%). After 14 weeks, average reductions were 0.26 log (10%), 0.38 log (30%), 0.46 log (50%), and 0.68 log (70%).

Figure 3: Long-term survival of B. subtilis spores in 2-propanol. Assessment of viability of B. subtilis spores after exposure to 2-propanol. Data are reported as logarithmic reduction factors RF = lg N0 – lg Na, where N0 is cfu/ml of control (water) and Na is cfu/ml in sample after exposure to the respective 2-propanol concentration at indicated contact times. The experiments were reproduced three times and data are given as mean values. Error bars represent standard deviations.

In-use contamination and stability of alcohol-based formulations

To determine the in-use contamination and stability of alcohol-based formulations used for hand disinfection and skin antisepsis, two typical alcohol-based products were investigated by repeated use under practical conditions over a period of 12 months. Microbiological and physicochemical data were determined. Aerobic spore-forming bacteria played a role as potential airborne contaminants, whereas strictly anaerobic spores were of no relevance (as described above), therefore, microbiological assessment throughout the in-use tests was focused on total viable aerobic count.

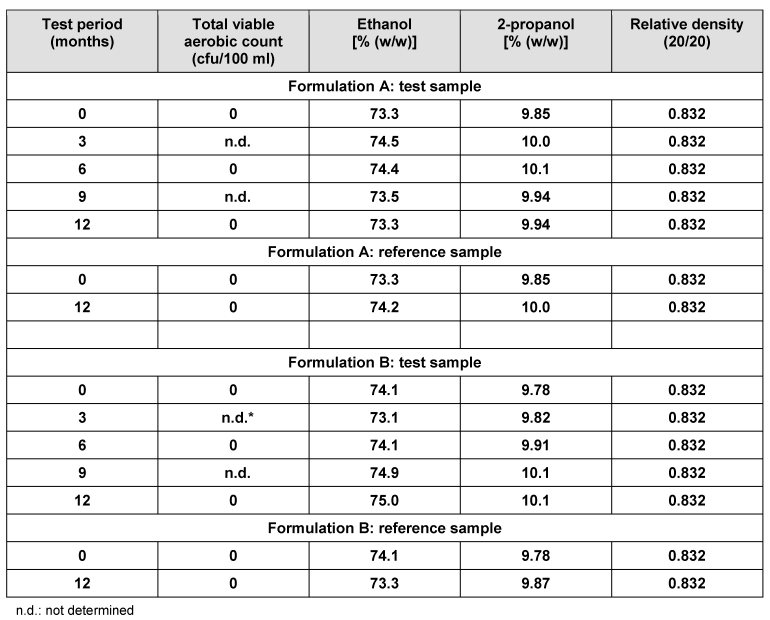

Table 6 [Tab. 6] shows the data obtained for the samples challenged in the in-use simulation, compared with the respective reference samples. At the outset, total viable aerobic count was 0 cfu/100 ml disinfectant, which remained unchanged after 6 and 12 months use. Assays for ethanol and 2-propanol indicated no significant variation over time. The same result was found for the relative density of the two typical formulations tested.

Table 6: In-use contamination and stability of alcohol-based formulations

Discussion

In our study in-use tests of two typical alcohol-based disinfectant formulations revealed no significant changes even when tested for 12 months. Neither microbial contamination nor significant changes in the physico-chemical data indicating changes in active compounds was detected. As we used typical formulations, it is implied that these results are valid for other alcohol-based formulations. These data correspond closely to those reported previously [13], where 50 100-ml pocket bottles were opened and left under normal environmental conditions for 3 days. Subsequent evaluation of aliquots from each bottle revealed no bacterial growth.

Furthermore, C2–C3 aliphatic alcohols have been demonstrated to account for a slow, but recognisable impairment of bacterial spores when tested at concentrations commonly used in hand disinfectants and skin antiseptics. This finding correlates with data from Setlow et al. who have described sporicidal efficacy of 70% ethanol at elevated temperature within as little as 2 h for B. subtilis spores, with reduction rates of ~2 log [20]. Decoating of spores was found to have no significant impact on killing of spores by 70% ethanol at 65°C. Release of dipicolinic acid (DPA) paralleled spore killing, and Setlow et al. [20] have proposed that loss of DPA and the associated core hydration are the underlying mechanism for the observed sporicidal efficacy. Our data regarding long-term survival of B. subtilis spores in C2–C3 aliphatic alcohols also revealed some impact on spore survival when tested for ~100 days at room temperature. 1-propanol was the most effective alcohol, followed by 2-propanol and ethanol. Observed differences in the efficacy of aliphatic alcohols may be attributed to the different lipophilicity of the three alcohols. 1-propanol as an unbranched C3-aliphatic alcohol is the most lipophilic molecule, whereas ethanol as a C2-aliphatic alcohol is the least lipophilic. Thus, penetration of the spore coat, which has been suggested for alcohols due to their small molecular size [9], [20], may differ for the aliphatic alcohols, with differences in efficacy regarding release of DPA, which has been proposed as the rate-limiting event in killing of B. subtilis spores [20]. However, further studies are needed to explain the observed long-term impact on spore survival of the different aliphatic alcohols.

Infections with anaerobic spore-forming bacteria due to contaminated antiseptics have not been reported, as far as we are aware. This agrees with our own findings, where no anaerobic spore-forming bacteria were detected.

In addition it has been demonstrated that sterility of the skin cannot be achieved using the known hand disinfectants and skin antiseptics [18], [19], [22]. Data from our laboratories indicate that spore-forming bacteria can be isolated from human skin (data not shown), which is consistent with previous findings [15], [21], [22]. Consequently, a maximum of 10 ml product on surgeons’ hands during disinfection [14], and <1 bacterial spore at the incision site in preoperative skin antisepsis, will not result in any additional bacterial spore burden on the patient’s skin, and can be considered safe.

Hoewever, Hsueh et al. have reported a nosocomial pseudo-epidemic caused by B. cereus [10]. Contaminated 70% ethanol was used in the hospital as a skin antiseptic and contamination was traced to contaminated 95% ethanol. Based on our data 95% ethanol does have no impact on survival of B. subtilis spores, even after 98 days contact time. This correlates well with the finding of Hsueh et al., who found that 95% ethanol was the source of the pseudo-epidemic [10]. However, they did not mention sterile filtration in their report and its omission was likely implicated in the pseudo-epidemic, underlining the importance of safe production processes including any auxiliary material.

In our study investigation of primary packaging material used throughout state-of-the-art production processes revealed only a maximum median of 0.02 cfu/ml for contamination with bacterial spores. Given a dosage of 10 ml applied for surgical hand disinfection or skin antiseptics, a median of 0.2 cfu/10 ml spore-forming bacteria can be considered as the maximum contamination risk associated with primary packaging material, thus not posing a public health risk.

In our study primary packaging material and use were not found to pose a significant contamination risk regarding bacterial spores. Thus state-of-the-art production processes of alcohol based hand rubs and antiseptics and subsequent use can be regarded safe. Based on the data of this study a microbial limit of <1 cfu/10 ml is suggested as a quality-control threshold for finished goods to ensure high quality production processes and safe products.

Notes

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Schülke & Mayr GmbH, Germany, Bode Chemie GmbH, Germany, Ecolab Deutschland GmbH, Germany, Lysoform Dr. Hans Rosemann GmbH, Germany, and B. Braun Melsungen AG, Germany. Irene Pauselius and Silke Erich are acknowledged for excellent technical assistance. Peter Goroncy-Bermes, Günter Kampf and Mirja Reichel are thanked for critical discussion of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

KS is employed by Schülke & Mayr GmbH, Norderstedt. BM is employed by Ecolab Deutschland GmbH, Düsseldorf. CO is employed by Bode Chemie GmbH, Hamburg. HJR is employed by Lysoform Dr. Hans Rosemann GmbH, Berlin. MH is employed by B. Braun Melsungen AG, Melsungen.

Funding

This study was funded by Schülke & Mayr GmbH, Germany, Bode Chemie GmbH, Germany, Ecolab Deutschland GmbH, Germany, Lysoform Dr. Hans Rosemann GmbH, Germany, and B. Braun Melsungen AG, Germany.

References

[1] Ali Y, Dohan JD, Fendler EJ, et al. Alcohols. In: Block SS, ed. Disinfection, Sterilization, and Preservation. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2001. p. 229-53.[2] Berger SA. Pseudobacteremia due to contaminated alcohol swabs. J Clin Microbiol. 1983 Oct;18(4):974-5.

[3] Bottone EJ. Bacillus cereus, a volatile human pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010 Apr;23(2):382-98. DOI: 10.1128/CMR.00073-09

[4] Caldeira D, David C, Sampaio C. Skin antiseptics in venous puncture-site disinfection for prevention of blood culture contamination: systematic review with meta-analysis. J Hosp Infect. 2011 Mar;77(3):223-32. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhin.2010.10.015

[5] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Notes from the field: Contamination of alcohol prep pads with Bacillus cereus group and Bacillus species--Colorado, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011 Mar 25;60(11):347.

[6] Craven SE, Blankenship LC. Activation and injury of Clostridium perfringens spores by alcohols. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985 Aug;50(2):249-56.

[7] European Committee for Standardization. European Standard EN 13704: Chemical disinfectants – quantitative suspension test for evaluation of sporicidal activity of chemical disinfectants used in food, industrial, domestic and institutional areas – test method and requirements (phase 2, step 1). 2002.

[8] European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines (EDQM). European Pharmacopoeia. 7th edition. 2010.

[9] Gerhardt P, Scherrer R, Black SH. Molecular sieving by dormant spore structures. In: Halvorson HO, et al, eds. Spores V. Washington DC: American Society for Microbiology; 1972. p. 68-76.

[10] Hsueh PR, Teng LJ, Yang PC, Pan HL, Ho SW, Luh KT. Nosocomial pseudoepidemic caused by Bacillus cereus traced to contaminated ethyl alcohol from a liquor factory. J Clin Microbiol. 1999 Jul;37(7):2280-4.

[11] Ihde DC, Armstrong D. Clinical spectrum of infection due to Bacillus species. Am J Med. 1973 Dec;55(6):839-45. DOI: 10.1016/0002-9343(73)90266-0

[12] International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Sampling procedures for inspection by attributes – Part 1: sampling schemes indexed by acceptance quality limit (AQL) for lot-by-lot inspection; Amendment 1. 2011.

[13] Kampf G, McDonald C, Ostermeyer C. Bacterial in-use contamination of an alcohol-based hand rub under accelerated test conditions. J Hosp Infect. 2005 Mar;59(3):271-2. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhin.2004.09.004

[14] Kampf G, Ostermeyer C. Influence of applied volume on efficacy of 3-minute surgical reference disinfection method prEN 12791. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004 Dec;70(12):7066-9. DOI: 10.1128/AEM.70.12.7066-7069.2004

[15] Kloos WE, Musselwhite MS. Distribution and persistence of Staphylococcus and Micrococcus species and other aerobic bacteria on human skin. Appl Microbiol. 1975 Sep;30(3):381-5.

[16] Logan NA, Popvic T, Hoffmaster A. Bacillus and other aerobic endospore-forming bacteria. In: Murray PR, Baron EJ, Pfaller MA, eds. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 7th ed. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology; 2007. p. 455-73.

[17] Popham DL, Helin J, Costello CE, Setlow P. Muramic lactam in peptidoglycan of Bacillus subtilis spores is required for spore outgrowth but not for spore dehydration or heat resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996 Dec 24;93(26):15405-10. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15405

[18] Raedler C, Lass-Flörl C, Pühringer F, Kolbitsch C, Lingnau W, Benzer A. Bacterial contamination of needles used for spinal and epidural anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 1999 Oct;83(4):657-8. DOI: 10.1093/bja/83.4.657

[19] Sato S, Sakuragi T, Dan K. Human skin flora as a potential source of epidural abscess. Anesthesiology. 1996 Dec;85(6):1276-82. DOI: 10.1097/00000542-199612000-00008

[20] Setlow B, Loshon CA, Genest PC, Cowan AE, Setlow C, Setlow P. Mechanisms of killing spores of Bacillus subtilis by acid, alkali and ethanol. J Appl Microbiol. 2002;92(2):362-75. DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2002.01540.x

[21] Sharma RK, Katoch K, Sharma VD, Shivannavar CT, Natarajan M, Katoch VM. Studies on microbial aerobic flora of skin in leprosy patients. Indian J Lepr. 1995 Jul-Sep;67(3):309-19.

[22] Suwanpimolkul G, Pongkumpai M, Suankratay C. A randomized trial of 2% chlorhexidine tincture compared with 10% aqueous povidone-iodine for venipuncture site disinfection: Effects on blood culture contamination rates. J Infect. 2008 May;56(5):354-9. DOI: 10.1016/j.jinf.2008.03.001

[23] World Health Organization. WHO guidelines on hand hygiene in health care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009.