[Depressive symptoms in unilateral and bilateral cochlear implant users]

Katharina Heinze-Köhler 1Effi Katharina Lehmann 1

Cynthia Glaubitz 1

Ulrich Hoppe 1

1 Cochlear Implant Center CICERO, University Hospital Erlangen, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Erlangen, Germany

Abstract

Background: Previous studies on depressive symptoms in cochlear implant (CI) users often considered small groups of unilateral or bilateral CI users separately. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to analyze and compare the extent of depressive symptoms in bilateral CI users and different groups of unilateral CI users within one study.

Methods: A total of 331 CI users were given a short form of the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-V) at an early stage of rehabilitation after surgery. These were subdivided into 45 bilateral CI users, 204 unilateral CI users with a hearing aid on the contralateral side, 25 unilateral CI users with a hearing impaired but unaided contralateral side, and 57 unilateral CI users with a normal hearing contralateral side. The influence of provision mode of the contralateral side, age, gender, and speech recognition with CI in the Freiburg Monosyllabic Word Test on the extent of depressive symptoms was examined.

Results: Bilateral CI users had significantly lower total BDI-V scores than the reference group of unilateral CI users with hearing aids on the contralateral side. Age and gender showed similar effects as in other studies, while speech recognition with CI showed no significant influence on the extent of depressive symptoms. The mean BDI-V total score of the overall sample of all CI users was within the normal range of the BDI-V.

Discussion: Bilateral CI, when indicated, seems to be associated with a low level of depressive symptoms. Possible explanations could be the rehabilitation already undergone after the first CI-provision as well as the relative exclusion of a further progression of hearing impairment in bilateral CI users.

Keywords

cochlear implant, depression, depressive symptoms, bilateral, CI rehabilitation

Introduction

Around 1.5 billion people worldwide are affected by hearing loss in various degrees [44]. As a result of impaired hearing, there have been many reports of decline of quality of life and mental health and an increase in depressive symptoms [1], [18], [21], [24], [40].

In cases of profound hearing loss that can no longer be compensated for with conventional sound-amplifying hearing aids, a cochlear implant (CI) can be considered if the medical and rehabilitative conditions are met [8], [16], [17].

Depressive symptoms in CI users

An early study that addressed the psychological effects of cochlear implantation found no differences in the amount of depressive symptoms in CI users preoperatively and one year postoperatively [11]. However, the number of CI users studied was comparatively small at 53, and individuals with pathological findings were excluded from CI surgery in advance. The provision mode of the contralateral side (e.g., hearing aid, CI, normal hearing) was not reported. Several later studies which did not include bilateral CI users except for one single person within one study, indicated a decrease in depressive symptoms after cochlear implantation [7], [23], [28], [34].

Bosdriesz and colleagues [6] found no difference in a depression scale between people with normal hearing and an equally small sample of 37 CI users who had already worn the CI for an average of five years, but whose duration of CI usage also showed a wide variability. Large groups of CI users are often difficult to reach for studies. However, they are necessary to ensure that an actual effect is not missed due to an insufficient number of cases.

Early studies often only included bilaterally deaf people or people with asymmetrical hearing loss with unilateral CI fitting. More recently, CI users with single-sided deafness and normal hearing on the contralateral side (SSD) and bilateral CI users have also been investigated with regard to the development of psychological variables after CI surgery. Improvements in hearing-related quality of life after implantation were found for all these patient groups [13], [29], [31]. Direct comparisons within one study between different groups of CI users – categorized according to binaural hearing status – showed no group differences in hearing-related quality of life postoperatively [19], [31], [39]. Depressive symptoms have so far been investigated only rarely within one study in both bilateral CI users and in unilateral CI users with asymmetrical hearing loss [19], [27]. There were no significant changes from preoperative to postoperative scores in either group [19] and no group differences at either time point [27].

Aims of the study

A larger amount of data on more specific areas of mental burden such as depressive symptoms in CI users is still lacking. The aim of the present study was to analyze the extent of depressive symptoms with an abbreviated form of the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-V) [37] in a population of patients with unilateral CI fitting and hearing aid or unaided hearing impairment on the contralateral side, SSD (unilateral CI and normal hearing on the contralateral side), and bilateral CI fitting in a German CI center. In the retrospective analysis, demographic variables and speech recognition with CI were also examined with regard to their relationship to the extent of depressive symptoms. The term extent of depressive symptoms is understood here as a weighting of the number of depressive symptoms with their frequency of occurrence as determined by the questionnaire. These are therefore metric values that can also be present without pathological findings.

Methods

Sample

All adult CI users who attended initial contact with a psychologist at the CICERO CI Center in Erlangen from January 2014 to December 2017 as part of basic and follow-up rehabilitative therapy were examined, regardless of the exact time at which this took place, and who consented to the processing and evaluation of the BDI-V questionnaire. The retrospective data analysis of the questionnaires was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nuremberg (No.: 162_17 Bc).

Participants were excluded if it was assumed that they did not sufficiently understand the questions of the BDI-V due to difficulties with the German written language. This was based on the clinical judgment of the test administrator. No other exclusion criteria were applied in order to obtain as comprehensive a picture as possible of the occurrence of depressive symptoms in CI users in everyday clinical practice.

A total of 331 CI users completed the BDI-V. During the period mentioned above, 368 people were fitted with 399 implants at CICERO. In addition, 91 people who underwent surgery before 2014 were still undergoing follow-up therapy. This means that 72% of all people undergoing basic or follow-up therapy in the above-mentioned period were covered by the BDI-V survey. With a desired test power of 80% and a significance level of α=0.05, the sample of 331 participants is suitable for recognizing even very small effect sizes of Cohen’s d=0.15 as significant in case of deviations of the BDI-V total score from the normative sample.

The sample of N=331 included 147 male and 184 female CI users. On average, the CI users were 58.68 years old (SD=15.05; min=18; max=85) at the time of questionnaire completion and had already completed an average of 5.82 (SD=6.034) treatment days. With the standardized procedures of basic and follow-up therapy in CICERO, this corresponds approximately to the time of one month after initial fitting of the CI processor. While 45 participants were fitted bilaterally with CIs, the majority of CI users, 286 participants, were fitted unilaterally. These were divided into 141 left-sided CI recipients and 145 right-sided CI recipients. On the contralateral side, the majority of unilateral CI users were fitted with a hearing aid (N=204). A further 25 unilateral CI users were hard of hearing or deaf on the opposite side but not fitted with a hearing aid or CI (unaided). A further 57 people were unilaterally deaf (SSD) and fitted with a CI and had normal hearing on the contralateral side. The distribution of gender and age in the subgroups can be found in Table 1 [Tab. 1]. A chi-square test was conducted to test the independence of gender and provision mode on the contralateral side (hearing aid, bilateral, SSD, unaided). This revealed no statistically significant relationship between gender and provision mode (χ2(3)=3.648; p=0.302). However, the groups according to provision mode differed significantly in terms of age (F=14.518; p<0.001).

BDI-V

The Beck Depression Inventory [2] is one of the most frequently used instruments worldwide for assessing depressive symptoms. Schmitt and Maes [37] developed a shortened German version (BDI-V) in order to make it more economical and less stressful for the person completing it, while maintaining the same quality criteria [36]. The correlation with the original version at total score level is given as r=0.91 and the internal consistency of the BDI-V is given as α=0.93 [36]. The assessed symptoms remained the same – except for weight loss – and include: mood/sadness, hopelessness/pessimism, self-dissatisfaction/failure, loss of pleasure, guilt feeling, feeling punished, self-hatred, self-criticism, self-punishment/suicidal thoughts, crying, irritability, social withdrawal/loss of interest, indecisiveness, body image, inability to work/loss of energy, sleep disturbance, fatigue, loss of appetite, hypochondria, and loss of sexual interest. Each of the twenty symptoms is queried with an item in the form of a statement such as “I am sad”. The written instructions for completing the questionnaire are: “This questionnaire is about your current feelings about life. For each question, please indicate how often you experience the mood or point of view mentioned.” The six-point frequency scale is represented numerically from 0 to 5, with the extreme values additionally coded verbally: 0/never and 5/almost always. By adding up the numerical values ticked in each case, a total score with a range of 0 to a maximum of 100 points can be formed. For total scores of 35 and above, Schmitt et al. [35] assume a probability of 92% that the person in question is actually affected by a depressive disorder (sensitivity). CI users who achieved such a score were recommended to undergo medical and psychotherapeutic examinations.

Freiburg Monosyllabic Word Test

Speech recognition with CI was measured using the Freiburg Monosyllabic Word Test [9]. All measurements were taken monaurally with CI. Depending on the degree of hearing impairment, the contralateral ear was deafened with earplugs and, if necessary, additionally with noise via headphones. The measurements were taken under quasi free-field conditions at 65 dBSPL. The loudspeakers were positioned frontally at a distance of one meter. The CI system was checked for technical integrity prior to the measurements. The Freiburg Monosyllabic Word Test is part of the clinical evaluation during the basic and follow-up therapy. For the present analysis, the detection rate achieved on the same treatment day on which the BDI-V was completed was recorded. If no value was available for the same day, the closest value within one month before or after the date of completion was selected. For bilateral CI users, the unilateral value measured on the side with better hearing was selected.

Data analysis

The statistical analysis of the data was performed with IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). The t-test was used to compare the CI users with the BDI-V normative sample [35]. After testing all variables with regard to the statistical preconditions, a multiple linear regression was used to check the influence of age, gender and the provision mode on the contralateral side (hearing aid, unaided, SSD, bilateral CI). Speech recognition rate in the Freiburg Monosyllabic Word Test and the number of treatment appointments already completed in the basic and follow-up therapy were correlated and therefore could not both be included as predictors in the regression. The treatment appointments that had already been completed were considered separately. Dummy coding was used to include the different provision modes and gender in the regression. An examination of the results revealed a slightly skewed distribution of the standardized residuals, so that bootstrapping was carried out with 1,000 samples. All p-values given refer to the bootstrapping procedure. The significance level was set to α=0.05.

Results

For all 331 CI users, the mean BDI-V total score was 19.67 (SD=15.66; min=0; max=88; women: M=22.11; SD=16.40; men: M=16.62; SD=14.14). With regard to the German gender-mixed normative sample [35], the mean value of the total sample corresponds to a percentile rank between 53.4 and 56.2. Out of 331 CI users, 50 (15.1%) achieved a total score of 35 or higher. The total score did not correlate with the number of treatment appointments in basic and follow-up therapy that were already completed by the time of the survey (r=–0.028; p=0.610).

A comparison of the mean BDI-V total score of the sample of CI users (M=19.67; SD=15.66) with the normative sample of the BDI-V (N=4494; M=20.4; SD=14.2) [35] revealed no significant difference (t(4823)=–0.896; p=0.370).

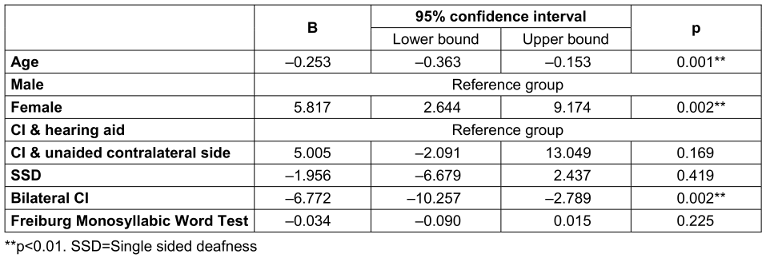

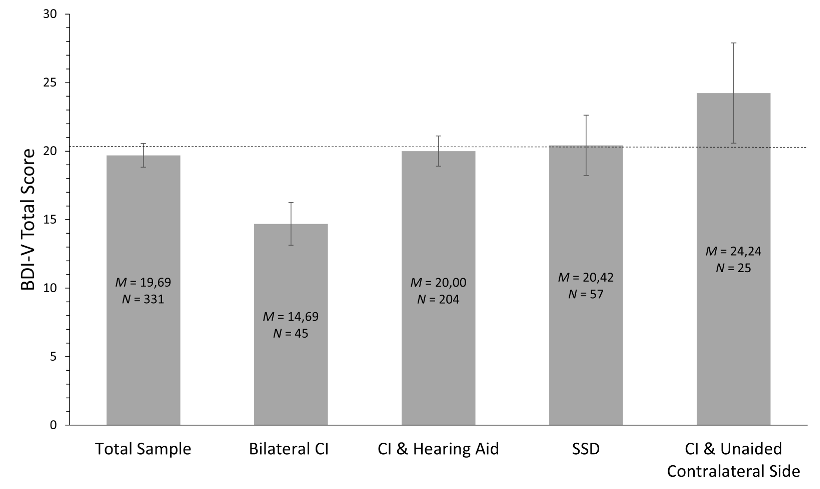

A multiple linear regression was conducted with the BDI-V total score as the dependent variable in order to check for a possible influence of hearing status and provision mode on the contralateral side. In addition to the provision mode, the known influencing factors of gender and age as well as speech recognition with CI measured with the Freiburg Monosyllabic Word Test were also included as predictors. R2=0.113 (p<0.001) was obtained for the overall model. An overview of the coefficients can be found in Table 2 [Tab. 2]. The gender variable female was positively weighted (B=5.817; p=0.002), i.e., female CI users achieved higher total scores. The age variable was negatively weighted, but with a small weight (B=–0.253; p<0.001). This means that CI users achieved lower total scores with increasing age. The Freiburg Monosyllabic Word Test variable showed no significant influence (B=–0.034; p=0.225). The result of the Freiburg Monosyllabic Word Test was on average 32.30% (SD=30.82) correctly recognized words at the time of measurement of an average of 5.82 treatment days (corresponds to approximately one month after initial fitting). Bilateral CI users achieved a lower total BDI-V score (M=14.69; SD=10.46) than all unilateral CI groups studied (see Figure 1 [Fig. 1]). A comparison with the reference group of those fitted with hearing aids on the contralateral side showed a significant influence of the bilateral fitting (B=–6.772; p=0.002). In the group of unilateral CI users, those who had a known but unaided hearing loss or deafness on the contralateral side achieved the highest descriptive total scores (M=24.24; SD=18.30). CI users with SSD achieved a mean total score of 20.42 (SD=16.56). Both groups did not differ significantly from the reference group of those fitted with hearing aids on the contralateral side (see Table 2 [Tab. 2]), who achieved a mean total score of 20 (SD=15.84) (see Figure 1 [Fig. 1]).

Due to the different age distribution in the groups, various control analyses were performed to ensure that the significant weight of the group variable Bilateral was not due to age. The correlation between these two variables was significant, but very low (r=–0.164; p=0.001). Repeating the regression analysis with only the predictor age resulted in a minimal change in the regression weight to B=–0.208 (p<0.001). Repeating the regression analysis with only the predictor Bilateral resulted in a change in the regression weight of the Bilateral group to B=–5.766 (p=0.021), but continued to be a significant effect. As a further control analysis, an analysis of covariance was performed with the BDI-V total score as the dependent variable, the group variable provision mode as a fixed factor, and the variable age as a covariate. A generally significant influence of the provision mode was found, taking age into account (F=4.376; p=0.005). Contrasts between the subgroups revealed a significant difference between the CI and hearing aid group and bilateral CI group (difference=–7.970; p=0.002). All other comparisons were not significant (lowest p=0.184).

In a next step, the mean total value of the Bilateral group was also compared with the mean value of the BDI-V normative sample. This showed a significantly lower mean value for bilateral CI users (t(4537)=–2.690; p=0.007). All other groups did not differ significantly from the normative sample (lowest p=0.178).

In order to additionally examine group differences in the BDI-V, differences in the occurrence of elevated total scores of 35 and above between the groups were evaluated. With these scores, the authors of the BDI-V assume a probability of 92% that a depressive disorder is present [35], whereby further assessments would be required for the actual diagnosis. In the Bilateral group, 4.4% of the participants had total scores of 35 and above. In the other groups, the proportion was 14.8% (CI and hearing aid), 17.2% (SSD) and 32% (contralateral side untreated). In the chi-square test, there was a significant relationship between the provision mode and the proportion of people with total scores of 35 and above (χ2(3)=9.776; p=0.021).

Discussion

Among CI users, bilateral CI users showed a lower level of depressive symptoms than the reference group with CI and hearing aid. However, unilateral CI users with untreated hearing loss on the contralateral side and CI users with SSD did not differ significantly from this reference group. The present study also shows that CI users do not differ from the representative normative sample [35] in terms of the extent of depressive symptoms, while the group of bilateral CI users has significantly lower BDI-V scores than the normative sample.

Hearing ability and extent of depressive symptoms – influence of the provision mode on the contralateral side

The measurable hearing performance of CI users showed a great variability, which can also be found in previous studies [5], [10], [30]. The hearing performance of unilateral CI users in everyday life is also strongly influenced by the hearing and provision status of the other side. In this study, the contralateral hearing performance of unilateral CI users was not quantified, but merely categorized into the variables SSD, hearing aid and unaided. These categories did not differ significantly from each other or from the normative sample in terms of the extent of depressive symptoms. CI users with an untreated hearing impairment on the contralateral side showed a slightly higher level of depressive symptoms. However, both in the group with an untreated contralateral side and in the large group of those fitted with hearing aid on the contralateral side, there is also considerable variability in the hearing performance of this contralateral side. Therefore, the reported result does not contradict the relationship between hearing ability and mental health found in other studies [1], [18], [24], [40], especially since the proportion of increased total scores with a significant group effect was highest in the group with an unaided hearing impaired contralateral side. Depressive symptoms can also have a negative effect on later speech recognition with CI, even if they are still within the normal range [15].

Bilateral CI users showed a lower average level of depressive symptoms compared to both the unilateral CI users and the normative sample of the BDI-V. Bichey and Miyamoto [4] reported increases in quality of life measured with the Health Utility Index (HUI) after bilateral CI provision, including in the emotion subscale, which includes depression and anxiety. While a meta-analysis by McRackan et al. [22] concludes that bilateral CI provision leads to increases in hearing-related but not general quality of life, especially such studies show an advantage of bilateral CI provision in quality of life using measures that include affectivity or depression [12], [25]. Péus et al. [29], on the other hand, reported stable frequency scores of depressive symptoms in a group of 29 bilateral CI users who were examined preoperatively, 6 months postoperatively of the sequential first CI and 6 months postoperatively of the sequential second CI. On average, these were within the normal range, but with a proportion of 34.4% requiring further treatment. For all other provision modes, an improvement in psychological measures post-operatively has been shown in the literature [13], [25], [28], but only a few direct comparisons have been made between different CI user groups with regard to depressive symptoms [19], [27]. The present results are not consistent with the results of these studies [19], [27]. However, it must be taken into account that here, a single survey was conducted at an unspecified early point in time within the postoperative baseline and follow-up therapy, while Ketterer et al. [19] compared preoperative and postoperative data and found no differences over time in the two groups of unilateral and bilateral CI users. The authors reported descriptively that the mean level of depressive symptoms in both groups was already low preoperatively compared to the norm of the test used [19]. Olze et al. [27] reported a lack of differences between the groups both preoperatively and postoperatively.

Comparable to the present data, Noble et al. [25] showed better scores of bilateral CI users compared to unilateral CI users with and without hearing aids in self-reported hearing-related emotional distress and hearing-related social isolation, which may be associated with depressive symptoms [38].

While other studies draw parallels between the objective hearing improvement with CI and improvements in psychological variables [7], [20], the extent of depressive symptoms was independent of the measured speech recognition rate with CI in the present cross-sectional assessment. This could be due to the fact that the questionnaire was given on average early within the baseline and follow-up therapy. At this time speech recognition was low on average, but also showed great variability. The low BDI-V total scores in bilateral CI users compared to fitting with CI and hearing aid must therefore be explained by other background variables. One possibility would be the stronger influence of objective speech intelligibility on the contralateral side. However, Ketterer et al. [19] showed a significant postoperative increase in monaural as well as binaural speech audiometry for both groups studied – unilateral CI users with asymmetrical hearing loss and bilateral CI users – with a descriptively comparable course of both measured values. In contrast, the depressive symptoms of both groups showed no changes over time [19]. Other possible variables described in the literature include a subjective improvement in hearing [22], which is only moderately related to objective measures [41], and improved suppression of tinnitus by ambient noise in CI users with tinnitus [26], [34]. Bosdriesz et al. [6] reported a low level of depressive symptoms in CI users in general, regardless of the degree of hearing impairment. They assumed, that the participation in the extensive rehabilitation program after CI provision could be a possible explanation [6]. In the present study, bilateral CI users showed a lower level of depressive symptoms regardless of the time point. Here, the basic and follow-up therapy that has usually already been completed after the first sequential cochlear implantation could have had a positive influence. Conversely, the lower level of depressive symptoms could also have had a positive influence on the decision to undergo a second implantation. This is beyond the scope of interpretation of the regression analysis conducted here and requires more detailed consideration in future studies. Bosdriesz et al. [6] cited as a further possible explanation for the comparable extent of depressive symptoms in CI users with normally hearing persons that hearing generally remains stable in the long term with CI fitting, whereas further deterioration cannot be ruled out with hearing aid fitting. In the present study, this stability applies in particular to those with bilateral CIs, which could explain their lower total BDI-V scores.

The group comparison also shows that psychological or subjective measures of rehabilitation success in CI users should take into account that hearing on the contralateral side has a decisive influence on everyday hearing, as this is usually binaural hearing. This should be taken into account in future studies.

Correlation with demographic variables

The higher BDI-V total scores found here for female CI users compared to male CI users correspond to the difference in the normative sample [35]. There is a higher prevalence of depressive disorders among women worldwide [43]. In addition, the presence of a hearing impairment has a negative impact on the prevalence, particularly among women [21]. Furthermore, the worldwide prevalence increases up to an age of around 60 years and then decreases again [43], whereby conversely, the normative sample of the BDI-V shows higher total scores for women under 21 and over 70 [35]. In contrast, the present sample of CI users showed a negative relationship between BDI-V total score and age, but with a very low weight, which would correspond to a reduction of 2.5 points in the total score per ten years increase in age. It must be taken into account that the group of CI users studied here was already 58 years old on average. The BDI-V could underestimate depressive symptoms due to a possible change in the symptom structure in the presence of depressive disorders at an older age [42]. However, the values of the normative sample and other studies with CI users using other depression measures suggest otherwise. Häußler et al. [13] found values without pathological findings in a depression questionnaire even before surgery in 20 CI users with SSD, who had a similar age structure and equally heterogeneous measurement times as in the present study. Poissant et al. [32] reported a reduction in depressive symptoms from pre- to post-implantation only in CI users over 70 years of age, but not in CI users under 60 years of age. Overall, CI provision may be a protective factor, particularly for older females, possibly by mitigating negative effects such as social isolation, which is associated with depressive symptoms and more closely associated with hearing impairment in females [38].

Limitations and strengths

A limitation of the comparison with the normative sample is that the normative data was published in 2006, while the data for this study was collected between 2014 and 2017. The use of the outdated normative data could have led to an over- or underestimation of the extent of depressive symptoms. In addition, persons with hearing impairments were not explicitly excluded from the normative sample. It is therefore possible that the comparison made here with the normative sample underestimates the extent of depressive symptoms in CI users and that a comparison with a verifiably normal-hearing control group would produce a different result. Bosdriesz et al. [6] carried out such a comparison and found no differences between CI users and normal hearing controls in a depression scale. In the study, however, the degree of hearing impairment was controlled in order to examine only the influence of the technical fitting. In addition, the classification of the severity of the hearing impairment was also based on a self-assessment by the participants.

Due to the size of the sample of CI users in the present study, it can be largely ruled out that an actual difference with clinically significant effect size was overlooked, so that previous studies with smaller numbers of CI users, which also found no difference, gain in importance [3], [6], [34]. However, a further limitation is that the depression scales and screening instruments used were different in all reported studies, which may limit the comparability of the studies with each other and with the present study. High correlations are reported for the BDI-V at least with the General Depression Scale [14] and the BDI original version [35]. A disadvantage of the BDI-V is the lack of a clear cut-off value for a diagnosis. For future studies, it would be desirable to determine a prevalence rate among CI users with the help of expert ratings. An initial indication of the additional influence of the provision mode here is the significantly different proportion of increased total scores of 35 points and above in the groups. In future studies, it would also be advisable to add other possible influencing factors such as tinnitus and other health data to a model in order to be able to record and control any confounding influences of these health-related variables.

As the groups were not selected to be representative, but rather all CI users within a period of four years were included, the comparability of the subgroups according to provision mode could not be guaranteed with regard to demographic variables. For example, people with bilateral CIs were descriptively, but not significantly, predominantly female and on average younger than people with CIs and hearing aids. These conditions tended to be associated with higher total scores in the overall sample, but bilateral CI recipients achieved lower total scores than unilateral CI recipients. This suggests an additional effect of bilateral CI provision on the extent of depressive symptoms.

Conclusion

In addition to studies that show a benefit from the provision of a second CI in objective audiological measures (e.g., [12], [19], [29]), the present study also shows a particularly low level of depressive symptoms for bilateral CI users. It should also be emphasized that the overall sample of CI users did not differ in terms of depressive symptoms from the normative sample of the questionnaire used, while increased depressive symptoms are reported in the literature for those with hearing aids only and those with impaired hearing but without hearing aids [18], [21], [24]. It must be taken into account that the causality is unclear due to the one-time survey. However, the result can be incorporated into the counseling of CI candidates to the extent that individual reasons for a decision against a CI should be queried with regard to causal depressive symptoms.

Notes

Compliance with ethical guidelines

K. Heinze-Köhler, E. K. Lehmann, C. Glaubitz and U. Hoppe declare that there is no conflict of interest.

All human studies described were performed with the approval of the responsible ethics committee (No.: 162_17 Bc), in accordance with national law and the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975 (in the current, revised version). Informed consent was obtained from all patients involved.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Carola Stöckert for support in data collection, Fiona Röhrig for support in data analysis and Dr. Armin Ströbel for methodological advice.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

[1] Arlinger S. Negative consequences of uncorrected hearing loss--a review. Int J Audiol. 2003 Jul;42(Suppl 2):2S17-20.[2] Beck AT, Steer RA. Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation Inc; 1987.

[3] Bergman P, Lyxell B, Harder H, Mäki-Torkko E. The Outcome of Unilateral Cochlear Implantation in Adults: Speech Recognition, Health-Related Quality of Life and Level of Anxiety and Depression: a One- and Three-Year Follow-Up Study. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020 Jul;24(3):e338-346. DOI: 10.1055/s-0039-3399540

[4] Bichey BG, Miyamoto RT. Outcomes in bilateral cochlear implantation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008 May;138(5):655-61. DOI: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.12.020

[5] Blamey P, Artieres F, Başkent D, Bergeron F, Beynon A, Burke E, Dillier N, Dowell R, Fraysse B, Gallégo S, Govaerts PJ, Green K, Huber AM, Kleine-Punte A, Maat B, Marx M, Mawman D, Mosnier I, O'Connor AF, O'Leary S, Rousset A, Schauwers K, Skarzynski H, Skarzynski PH, Sterkers O, Terranti A, Truy E, Van de Heyning P, Venail F, Vincent C, Lazard DS. Factors affecting auditory performance of postlinguistically deaf adults using cochlear implants: an update with 2251 patients. Audiol Neurootol. 2013;18(1):36-47. DOI: 10.1159/000343189

[6] Bosdriesz JR, Stam M, Smits C, Kramer SE. Psychosocial health of cochlear implant users compared to that of adults with and without hearing aids: Results of a nationwide cohort study. Clin Otolaryngol. 2018 Jun;43(3):828-34. DOI: 10.1111/coa.13055

[7] Brüggemann P, Szczepek AJ, Klee K, Gräbel S, Mazurek B, Olze H. In Patients Undergoing Cochlear Implantation, Psychological Burden Affects Tinnitus and the Overall Outcome of Auditory Rehabilitation. Front Hum Neurosci. 2017 May 5;11:226. DOI: 10.3389/fnhum.2017.00226

[8] Deutsche Gesellschaft für Hals-Nasen-Ohren-Heilkunde, Kopf- und Hals-Chirurgie e. V. S2k-Leitlinie Cochlea-Implantat Versorgung. Version 3.0. Register-Nr.: 017-071. AWMF; 2020. Available from: https://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/017-071.html

[9] DIN 45621:1973–10 Wörter für Gehörprüfung mit Sprache. Berlin: Beuth Verlag; 1973.

[10] Finley CC, Holden TA, Holden LK, Whiting BR, Chole RA, Neely GJ, Hullar TE, Skinner MW. Role of electrode placement as a contributor to variability in cochlear implant outcomes. Otol Neurotol. 2008 Oct;29(7):920-8. DOI: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e318184f492

[11] Haas LJ. Psychological safety of a multiple channel cochlear implant device. Psychological aspects of a clinical trial. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1990;6(3):421-9. DOI: 10.1017/s0266462300001021

[12] Härkönen K, Kivekäs I, Rautiainen M, Kotti V, Sivonen V, Vasama JP. Sequential bilateral cochlear implantation improves working performance, quality of life, and quality of hearing. Acta Otolaryngol. 2015 May;135(5):440-6. DOI: 10.3109/00016489.2014.990056

[13] Häußler SM, Knopke S, Dudka S, Gräbel S, Ketterer MC, Battmer RD, Ernst A, Olze H. Verbesserung von Tinnitusdistress, Lebensqualität und psychologischen Komorbiditäten durch Cochleaimplantation einseitig ertaubter Patienten [Improvement in tinnitus distress, health-related quality of life and psychological comorbidities by cochlear implantation in single-sided deaf patients]. HNO. 2019 Nov;67(11):863-73. DOI: 10.1007/s00106-019-0706-7

[14] Hautzinger M, Bailer M. Allgemeine Depressions Skala. Weinheim: Beltz; 1993.

[15] Heinze-Köhler K, Lehmann EK, Hoppe U. Depressive symptoms affect short- and long-term speech recognition outcome in cochlear implant users. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021 Feb;278(2):345-51. DOI: 10.1007/s00405-020-06096-3

[16] Hoppe U, Hocke T, Hast A, Iro H. Cochlear Implantation in Candidates With Moderate-to-Severe Hearing Loss and Poor Speech Perception. Laryngoscope. 2021 Mar;131(3):E940-E945. DOI: 10.1002/lary.28771

[17] Hoppe U, Hocke T, Hast A, Iro H. Das maximale Einsilberverstehen als Prädiktor für das Sprachverstehen mit Cochleaimplantat [Maximum monosyllabic score as a predictor for cochlear implant outcome]. HNO. 2019 Mar;67(3):199-206. DOI: 10.1007/s00106-018-0605-3

[18] Keidser G, Seeto M, Rudner M, Hygge S, Rönnberg J. On the relationship between functional hearing and depression. Int J Audiol. 2015;54(10):653-64. DOI: 10.3109/14992027.2015.1046503

[19] Ketterer MC, Häussler SM, Hildenbrand T, Speck I, Peus D, Rosner B, Knopke S, Graebel S, Olze H. Binaural Hearing Rehabilitation Improves Speech Perception, Quality of Life, Tinnitus Distress, and Psychological Comorbidities. Otol Neurotol. 2020 Jun;41(5):e563-e574. DOI: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000002590

[20] Knutson JF, Murray KT, Husarek S, Westerhouse K, Woodworth G, Gantz BJ, Tyler RS. Psychological change over 54 months of cochlear implant use. Ear Hear. 1998 Jun;19(3):191-201. DOI: 10.1097/00003446-199806000-00003

[21] Li CM, Zhang X, Hoffman HJ, Cotch MF, Themann CL, Wilson MR. Hearing impairment associated with depression in US adults, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005-2010. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014 Apr;140(4):293-302. DOI: 10.1001/jamaoto.2014.42

[22] McRackan TR, Fabie JE, Bhenswala PN, Nguyen SA, Dubno JR. General Health Quality of Life Instruments Underestimate the Impact of Bilateral Cochlear Implantation. Otol Neurotol. 2019 Jul;40(6):745-53. DOI: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000002225

[23] Mosnier I, Bebear JP, Marx M, Fraysse B, Truy E, Lina-Granade G, Mondain M, Sterkers-Artières F, Bordure P, Robier A, Godey B, Meyer B, Frachet B, Poncet-Wallet C, Bouccara D, Sterkers O. Improvement of cognitive function after cochlear implantation in elderly patients. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015 May 1;141(5):442-50. DOI: 10.1001/jamaoto.2015.129

[24] Nachtegaal J, Smit JH, Smits C, Bezemer PD, van Beek JH, Festen JM, Kramer SE. The association between hearing status and psychosocial health before the age of 70 years: results from an internet-based national survey on hearing. Ear Hear. 2009 Jun;30(3):302-12. DOI: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31819c6e01

[25] Noble W, Tyler R, Dunn C, Bhullar N. Hearing handicap ratings among different profiles of adult cochlear implant users. Ear Hear. 2008 Jan;29(1):112-20. DOI: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31815d6da8

[26] Olze H, Gräbel S, Haupt H, Förster U, Mazurek B. Extra benefit of a second cochlear implant with respect to health-related quality of life and tinnitus. Otol Neurotol. 2012 Sep;33(7):1169-75. DOI: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e31825e799f

[27] Olze H, Ketterer MC, Péus D, Häußler SM, Hildebrandt L, Gräbel S, Szczepek AJ. Effects of auditory rehabilitation with cochlear implant on tinnitus prevalence and distress, health-related quality of life, subjective hearing and psychological comorbidities: Comparative analysis of patients with asymmetric hearing loss (AHL), double-sided (bilateral) deafness (DSD), and single-sided (unilateral) deafness (SSD). Front Neurol. 2023 Jan 12;13:1089610. DOI: 10.3389/fneur.2022.1089610

[28] Olze H, Szczepek AJ, Haupt H, Förster U, Zirke N, Gräbel S, Mazurek B. Cochlear implantation has a positive influence on quality of life, tinnitus, and psychological comorbidity. Laryngoscope. 2011 Oct;121(10):2220-7. DOI: 10.1002/lary.22145

[29] Péus D, Pfluger A, Häussler SM, Knopke S, Ketterer MC, Szczepek AJ, Gräbel S, Olze H. Single-centre experience and practical considerations of the benefit of a second cochlear implant in bilaterally deaf adults. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021 Jul;278(7):2289-96. DOI: 10.1007/s00405-020-06315-x

[30] Pisoni DB, Kronenberger WG, Harris MS, Moberly AC. Three challenges for future research on cochlear implants. World J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018 Jan 2;3(4):240-54. DOI: 10.1016/j.wjorl.2017.12.010

[31] Plath M, Marienfeld T, Sand M, van de Weyer PS, Praetorius M, Plinkert PK, Baumann I, Zaoui K. Prospective study on health-related quality of life in patients before and after cochlear implantation. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2022 Jan;279(1):115-25. DOI: 10.1007/s00405-021-06631-w

[32] Poissant SF, Beaudoin F, Huang J, Brodsky J, Lee DJ. Impact of cochlear implantation on speech understanding, depression, and loneliness in the elderly. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008 Aug;37(4):488-94.

[33] Rembar SH, Lind O, Romundstad P, Helvik AS. Psychological well-being among cochlear implant users: a comparison with the general population. Cochlear Implants Int. 2012 Feb;13(1):41-9. DOI: 10.1179/1754762810Y.0000000008

[34] Sarac ET, Ozbal Batuk M, Batuk IT, Okuyucu S. Effects of Cochlear Implantation on Tinnitus and Depression. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2020;82(4):209-15. DOI: 10.1159/000508137

[35] Schmitt M, Altstötter-Gleich C, Hinz A, Maes J, Brähler E. Normwerte für das Vereinfachte Beck-Depressions-Inventar (BDI-V) in der Allgemeinbevölkerung. Diagnostica. 2006;52(2):51-9. DOI: 10.1026/0012-1924.52.2.51

[36] Schmitt M, Beckmann M, Dusi D, Maes J, Schiller A, Schonauer K. Messgüte des vereinfachten Beck-Depressions-Inventars (BDI-V). Diagnostica. 2003;49(4):147-56. DOI: 10.1026//0012-1924.49.4.147

[37] Schmitt M, Maes J. Vorschlag zur Vereinfachung des Beck-Depressions-Inventars (BDI). Diagnostica. 2000;46(1):38-46. DOI: 10.1026//0012-1924.46.1.38

[38] Shukla A, Harper M, Pedersen E, Goman A, Suen JJ, Price C, Applebaum J, Hoyer M, Lin FR, Reed NS. Hearing Loss, Loneliness, and Social Isolation: A Systematic Review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020 May;162(5):622-33. DOI: 10.1177/0194599820910377

[39] Smulders YE, van Zon A, Stegeman I, Rinia AB, Van Zanten GA, Stokroos RJ, Hendrice N, Free RH, Maat B, Frijns JH, Briaire JJ, Mylanus EA, Huinck WJ, Smit AL, Topsakal V, Tange RA, Grolman W. Comparison of Bilateral and Unilateral Cochlear Implantation in Adults: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016 Mar;142(3):249-56. DOI: 10.1001/jamaoto.2015.3305

[40] Tambs K. Moderate effects of hearing loss on mental health and subjective well-being: results from the Nord-Trøndelag Hearing Loss Study. Psychosom Med. 2004 Sep-Oct;66(5):776-82. DOI: 10.1097/01.psy.0000133328.03596.fb

[41] Volleth N, Hast A, Lehmann EK, Hoppe U. Subjektive Hörverbesserung durch Cochleaimplantatversorgung [Subjective improvement of hearing through cochlear implantation]. HNO. 2018 Aug;66(8):613-20. DOI: 10.1007/s00106-018-0529-y

[42] Weyerer S. Epidemiologie der Altersdepression. In: Fellgiebel A, Hautzinger M, editors. Altersdepression. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2017. p. 3-11. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-662-53697-1_1

[43] World Health Organization. Depression and other common mental disorders: Global health estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017.

[44] World Health Organization. World report on hearing. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021.