[Eintagesprävalenz wichtiger bakterieller Problemerreger in vier Krankenhäusern der Regelversorgung und fünf Krankenhäusern der Maximalversorgung in Deutschland – Ergebnisse einer Pilotstudie der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Krankenhaushygiene (DGKH)]

Axel Kramer 1Sylvia Ryll 1

Christian Wegner 1

Lutz Jatzwauk 2

Walter Popp 3

Nils-Olaf Hübner 1

1 Institute of Hygiene and Environmental Medicine Greifswald, University Medicine, Greifswald, Germany

2 Department of Hospital Hygiene and Environmental Protection, University Medical Center, Dresden, Germany

3 Hospital Hygiene, University Medical Center, Essen, Germany

Zusammenfassung

Zielsetzung: In 5 Krankenhäusern der Maximalversorgung und 4 Krankenhäusern der Regelversorgung wurde am 10.2.2010 eine Eintagesprävalenzstudie zum Vorkommen bakterieller Problemerreger durchgeführt, um Prävalenzdaten für unterschiedliche Regionen zu generieren, da insbesondere für ESBL, multiresistente Pseudomonas spp. und Acinetobacter spp. sowie Clostridium difficile spp. kaum Daten für Deutschland vorliegen.

Methode: Mittels Fragenbogen wurden der Versorgungstyp der Einrichtung, die Ausstattung mit Hygienefachpersonal, die Durchführung eines MRSA Screenings und die mikrobiologische Versorgung sowie die Prävalenz fünf bakterieller Problemerreger in den Bereichen Intensivtherapie, Chirurgie und Innere Medizin erfasst.

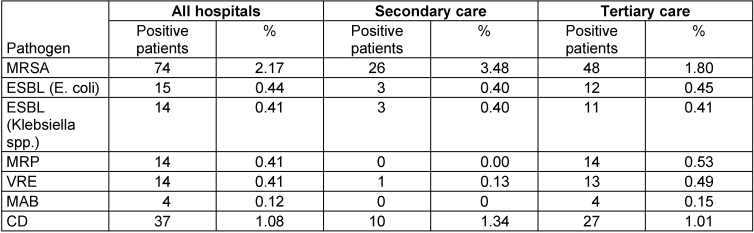

Ergebnisse: Insgesamt wurden 3411 Patienten analysiert. In den Krankenhäusern der Maximalversorgung wurden folgende Prävalenzen ermittelt: MRSA 1,8%, ESBL E. coli 0,45%, ESBL Klebsiella spp. 0,41%, multiresistente Pseudomonaden 0,53%, multiresistente Acinetobacter spp. 0,15%, VRE 0,49% und toxinbildende C. difficile 1,01%. In den Krankenhäusern der Regelversorgung ergaben sich folgende Prävalenzen: MRSA 3,48%, ESBL E. coli 0,4%, ESBL Klebsiella spp. 0,4%, multiresistente Pseudomonas spp. 0%, multiresistente Acinetobacter spp. 0%, VRE 0,13% und toxinbildende C. difficile 1,34%.

Diskussion: Die MRSA Prävalenz liegt in der Größenordnung anderer in den letzten Jahren veröffentlichter Prävalenzerhebungen, aber deutlich über den Prävalenzdaten des Krankenhaus-Infektions-Surveillance-Systems. Da für die anderen Problemerreger für Deutschland keine Prävalenzdaten recherchiert werden konnten, stehen zum Vergleich nur die ITS KISS Daten für den Zeitraum 2010 zur Verfügung, auch hier sind die in der vorliegenden Studie erhobenen Prävalenzen für MRSA, VRE und ESBL deutlich höher. Ob das ein zufälliger Effekt ist oder auf einem systematischen Fehler im KISS beruht, kann aus diesen Daten nicht geschlossen werden.

Schlussfolgerung: Die Ergebnisse der Eintagesprävalenzstudie zeigen, dass sich die Prävalenz bakterieller Problemerreger zwischen verschiedenen Einrichtungen deutlich unterscheidet. Das kann durch regionale Faktoren, den Versorgungsauftrag des Krankenhauses sowie methodisch bedingt sein. Trotzdem sind die Prävalenzen vergleichbar mit anderen Punktprävalenzdaten, aber deutlich höher als aus den Daten des KISS zu erwarten gewesen wäre.

Da die Erhebung einer Eintages-Punkt-Prävalenz ohne großen Aufwand realisierbar ist, erscheint es sinnvoll, derartige Erhebungen jeweils auf denselben Stichtag bezogen, auszuweiten, um repräsentative Daten für Deutschland zu generieren. Durch solche Initiativen können Medizinische Fachgesellschaften wie die DGKH einen einfachen aber wichtigen Beitrag zur Beschreibung der Epidemiologie wichtiger Pathogene leisten.

Schlüsselwörter

Eintagesprävalenz, MRSA, ESBL E. coli, ESBL Klebsiella spp., multiresistente Pseudomonas spp., multiresistente Acinetobacter spp., VRE, toxinbildende C. difficile, Hygienefachpersonal, DGKH

Introduction

In 2010, the German Society for Hospital Hygiene (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Krankenhaushygiene, DGKH) launched a study to assess the prevalence of five emerging bacterial pathogens in volunteering hospitals to help to provide data on the epidemiology of carrier-ship and infections with these emerging nosocomial pathogens. The study was designed as a one-day point-prevalence study and conducted on the on the 10th of February 2010.

Method

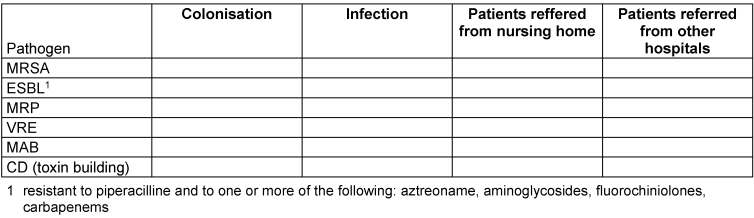

For participating hospitals, the level of care, staffing with infection prevention personnel, availability of a MRSA-screening and microbiological support was assessed by a basic questionnaire and the prevalence of the five emerging bacterial pathogens: Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), extended-spectrum-lactamase-building (ESBL) Gram negative organisms, multiresistant Pseudomonas (MRP) and Acinetobacter species (MAB), Vancomycin-resistant Entoerococcus species (VRE) and toxin-building Clostridium difficile (CD) in intensive care, surgical and medical wards by three identical questionnaires (Table 1 [Tab. 1]).

Table 1: Questionnaire for the assessment of the prevalence of five emerging bacterial pathogens in patients on the day of the point prevalence study

Results

Participating hospitals

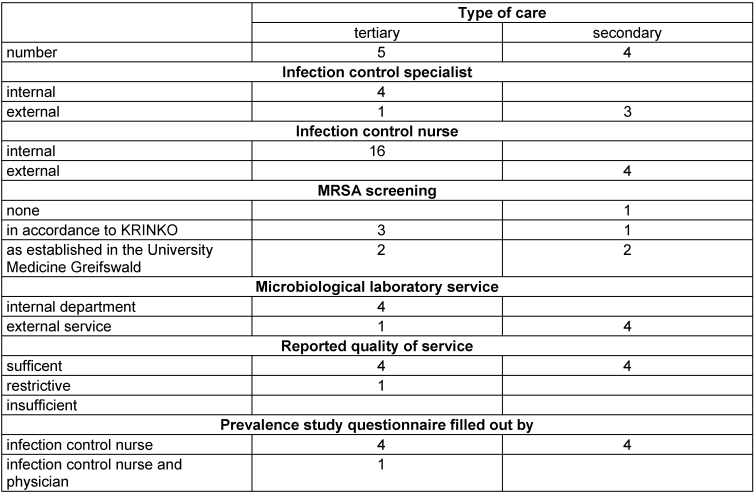

Five tertiary and four secondary care hospitals participated in the study (Table 2 [Tab. 2]). Overall, 3411 patients were included. Questionnaires were mostly filled out by infection control nurses. None of the participating hospitals reported logistical problems.

Table 2: Selected indicators of structure quality and MRSA screening policy in the participating hospitals

Infection prevention personnel

Four tertiary care hospitals had an own infection control specialist and one was serviced by an external specialist. In contrast, one secondary care hospital had no infection control specialist and the other three had an external one.

All tertiary care hospitals had own infection control nurses: three hospitals had four, one three and one only one nurse. In secondary care hospitals, however, had only one, external, infection control nurse each (Table 2 [Tab. 2]). With one exception, the microbiological service was reported as “sufficient”.

MRSA screening

Quality of MRSA screening regimes differed markedly between hospitals. In three tertiary hospitals, patients were screened in accordance with the recommendations by the Commission for Hospital Hygiene and Infection Prevention at the Robert Koch Institute (KRINKO) [1] if they had two or more risk factors. In two hospitals, patients with one or more risk factor and all patients admitted to intensive care wards were screened as established in the University Medicine Greifswald (“Greifswald model”) [2], [3]. In one tertiary care hospital an ESBL-screening for urological patient is established, too.

Prevalences

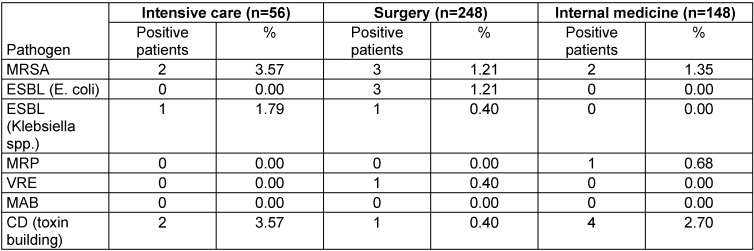

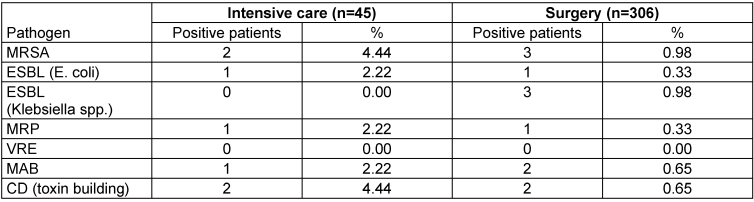

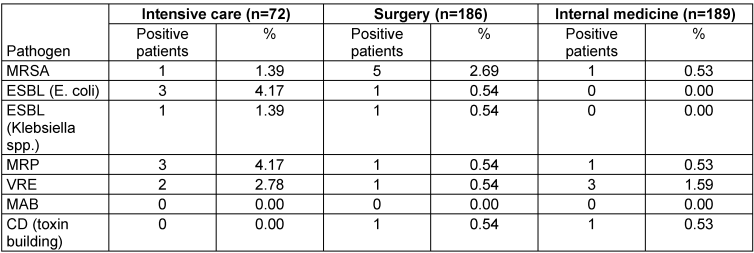

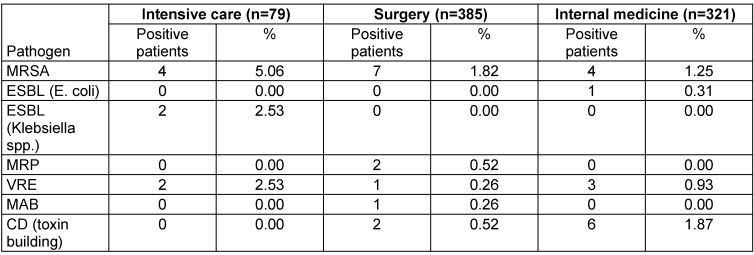

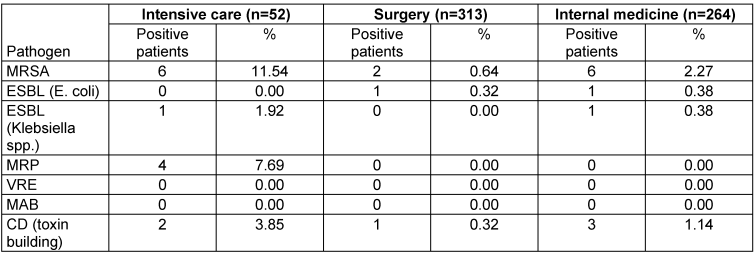

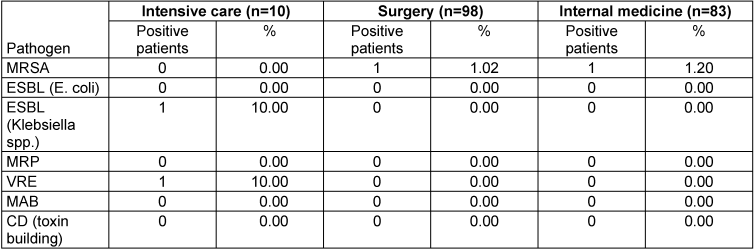

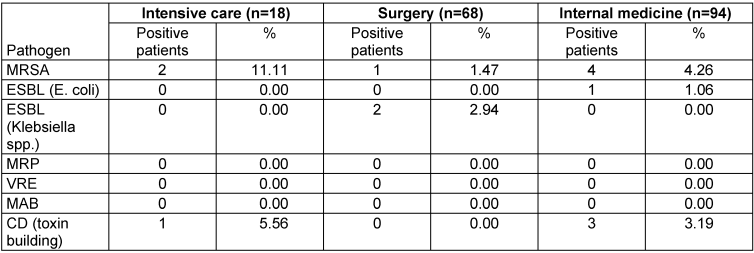

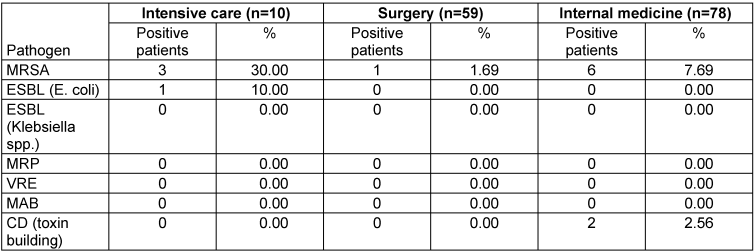

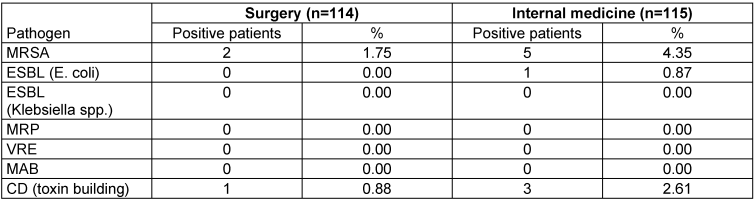

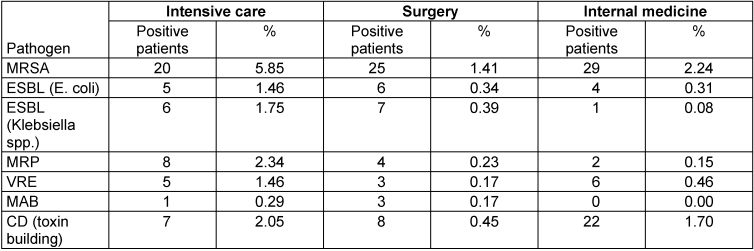

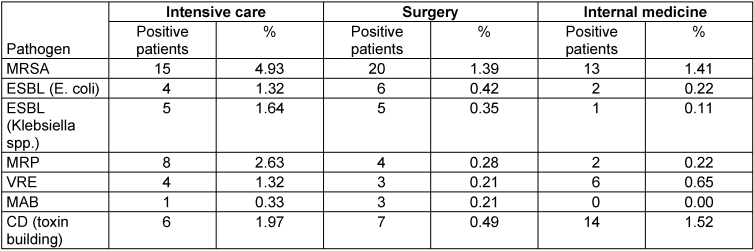

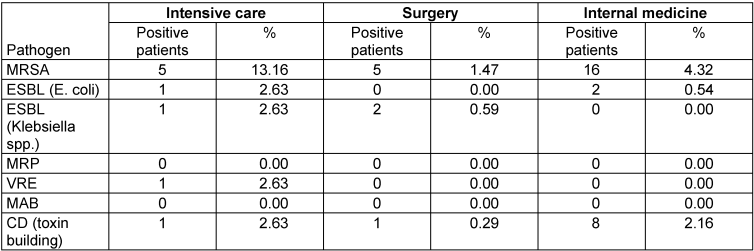

MRSA was the most frequently reported pathogen in all participating hospitals (Table 3 [Tab. 3], Table 4 [Tab. 4], Table 5 [Tab. 5], Table 6 [Tab. 6], Table 7 [Tab. 7], Table 8 [Tab. 8], Table 9 [Tab. 9], Table 10 [Tab. 10], Table 11 [Tab. 11]), followed by CD and ESBL. No patient with CD was reported to require intensive care.

Table 3: Prevalence data for tertiary care hospital No. 1

Table 4: Prevalence for tertiary care hospital No. 2

Table 5: Prevalence data for tertiary care hospital No. 3

Table 6: Prevalence data for tertiary care hospital No. 4

Table 7: Prevalence data for tertiary care hospital No. 5

Table 8: Prevalence data for secondary care hospital No. 6

Table 9: Prevalence data for secondary care hospital No. 7

Table 10: Prevalence data for secondary care hospital No. 8

Table 11: Prevalence data for secondary care hospital No. 9

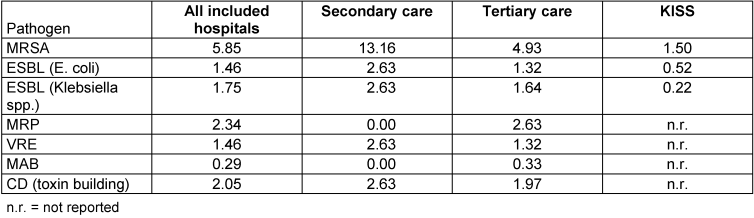

Seen over all departments and hospitals, MRSA and CD had a higher prevalence in secondary care hospitals in comparison to tertiary care. ESBL prevalence was comparable for both groups and MRP and VRE were more frequently reported in tertiary care hospitals. MAB were reported in tertiary care hospitals only (Table 12 [Tab. 12], Table 13 [Tab. 13], Table 14 [Tab. 14], Table 15 [Tab. 15]).

Table 12: Comparison of prevalences in secondary and tertiary hospitals for all included departments

Table 13: Comparison of prevalences in intensive care, surgical and medical departments for all included hospitals

Table 14: Comparison of prevalences in intensive care, surgical and medical departments for tertiary care hospitals

Table 15: Comparison of prevalences in intensive care, surgical and medical departments for secondary care hospitals

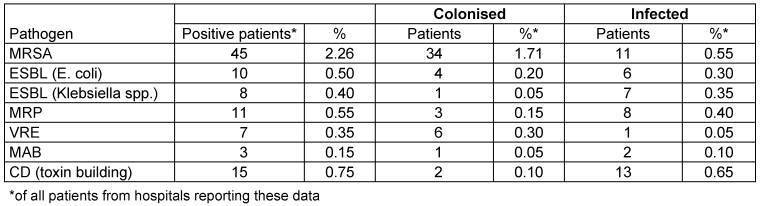

Some hospitals additionally provided refined data that allow to between infection and colonisation (Table 16 [Tab. 16]).

Table 16: Refined data for infected and colonised patients

Discussion

Data on the epidemiology of emerging bacterial pathogens with significant impact on hospital epidemiology are still sparse in Germany. Voluntary prevalence studies as this one initiated by the DGKH are an attempt to improve the epidemiological knowledge in this field. While this type of study has several limitations, as it gives only a momentary image of the situation and the data can be compared to data gathered with the same method only, it still is an inexpensive, convenient and feasible way to generate valuable data and sensitize health care workers for the situation on their wards.

The overall prevalence of MRSA, the post frequently reported pathogen in this study, was 2.2%. While not directly comparable to other studies, this seems to be in the range of other surveys as from the county of Höxter in 2008 (3.4%) [4], the EUREGIO MRSA-net Twente/Münsterland in 2006 (1.6% for the German part) [5], the city of Essen in 2009 (2% in hospitals) [6] and the Saarland 2010 (2.18%) [7].

In the four secondary care hospitals the MRSA prevalence was 3.7% and therefore much higher as in the tertiary care hospitals (1.74%), which was unexpected.

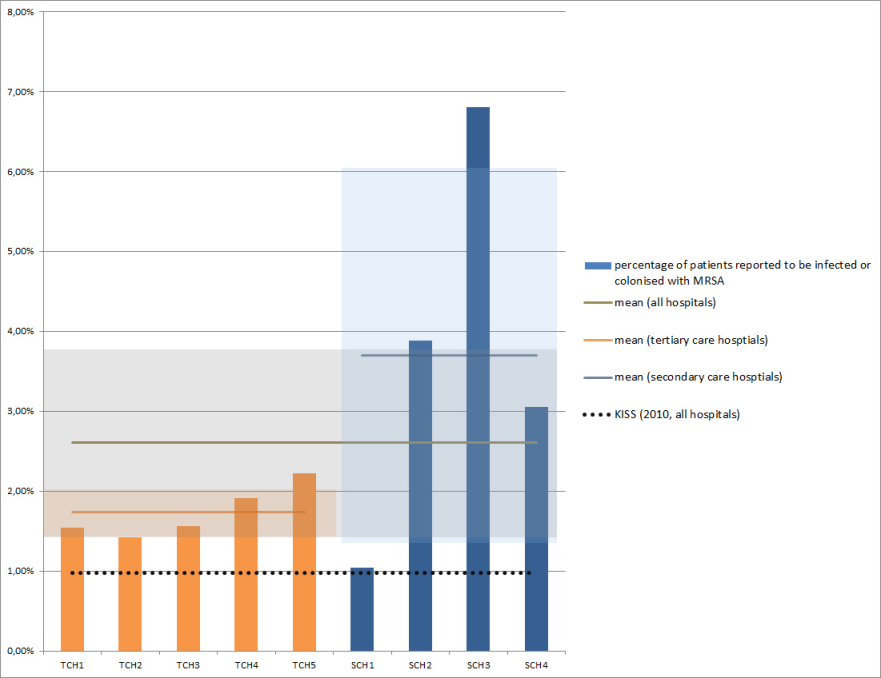

Remarkably, all five studies report much higher prevalences than one would expect from the data provided by the German KISS (Krankenhaus-Infektions-Surveillance-System), that reported a mean prevalence of 0.98% for all participating hospitals (n=268) only, 0.96% for hospitals >600 beds and 1.00% for hospitals <600 beds in 2010 (Figure 1 [Fig. 1]) [8].

Figure 1: Prevalences of MRSA for all participating hospitals and departments (TCH = tertiary care hospitals, SCH = secondary care hospitals), means and 95% confidence intervals for all, tertiary and secondary care hospitals in comparison to MRSA-KISS

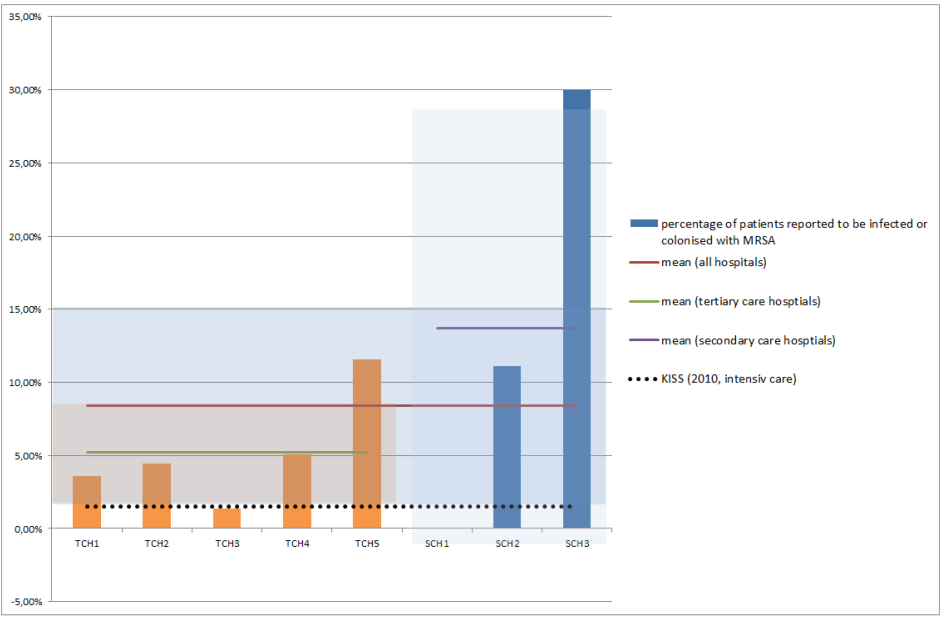

Our initial consideration was, that this may be due to the fact that our prevalence study was conducted on surgical, medical and intensive care wards only, and that therefore intensive care (which has a relatively high MRSA-prevalence) is overweighed in comparison to the KISS data that includes all wards. However, the MRSA prevalence on intensive care units in this study is also much higher than the one reported by the ITS-KISS with 8.39% versus 1.5%, respectively (Figure 2 [Fig. 2]) [9].

Figure 2: Prevalences of MRSA for intensive care units from all participating hospitals (TCH = tertiary care hospitals, SCH = secondary care hospitals), means and 95% confidence intervals for all, tertiary and secondary care hospitals in comparison to ITS-KISS

Unfortunately, the MRSA-KISS system does not support individual statistics for other medical specialities. Whether the obvious differences between the results from all five prevalence studies and the KISS is by chance or indicates a systematic underreporting in the KISS remains unclear.

As the tertiary care hospital number 5 provided the whole-year for MRSA-prevalence additionally, the point-prevalence and the overall prevalence for 2010 can be compared for this hospital. With 2.23%, the point-prevalence was higher than the mean prevalence for 2010 (1.28%), which is, again, much higher than to be expected from the MRSA-KISS. Just as for the relation between the prevalence studies and the KISS-data discussed above, this could be caused by overweighting intensive care units (see above). Still, the prevalence data from the intensive care units is also much higher (3.58%) than to be expected from ITS-KISS (1.5%), underlying the need to validate the KISS results by external studies [9], [10].

Compared to MRSA, the prevalence of the other included pathogens was much lower, but they were still frequently reported especially on ICUs. Table 17 [Tab. 17] compares the prevalences found in participating ICUs between levels of care and data from the ITS-KISS, if available [9]. Again, prevalences for all levels of care and all pathogens were much higher as to be expected from the KISS. For CD, too, the prevalence found in our study was more than twice as high (1.08%) as expected based on the CDAD-KISS (0.46%) [11].

Table 17: Prevalences (%) of included pathogens on intensive care units participating in the prevalence study and from ITS-KISS (all types, 2010)

Conclusion

As previously reported by other authors, our study shows that prevalences of emerging bacterial pathogens differ markedly between regions, departments and hospitals. While one-day point-prevalences have to be interpreted with caution, the prevalences found fit well to other prevalence studies from the last years. Remarkably, all of those studies have found much higher prevalences than to be expected from the data of the KISS. Further studies are needed to show whether this was by chance alone or indicates a systematic underreporting in the KISS.

Voluntary point-prevalence studies from routine data have been shown to be an inexpensive way to generate valuable data. By such initiatives, scientific societies as the DGKH can take part in collecting valuable epidemiological data. Future studies, using a fixed day and protocol, could be an interesting tool to describe the epidemiology of emerging bacterial pathogens and verify data from other sources.

Notes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

[1] Empfehlung zur Prävention und Kontrolle von Methicillin-resistenten Staphylococcus aureus-Stämmen (MRSA) in Krankenhäusern und anderen medizinischen Einrichtungen Mitteilung der Kommission für Krankenhaushygiene und Infektionsprävention am RKI. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 1999;42(12):954-8. DOI: 10.1007/s001030050227[2] Bartels C, Ewer R, Steinmetz I, Kramer A. Methicillin-Resistente Staphylokokken: Frühes Screening senkt die Zahl der Infektionen. Dtsch Ärztebl. 2008;105(13):A-672. Available from: http://www.aerzteblatt.de/v4/archiv/artikel.asp?id=59521

[3] Hübner NO, Kramer A, Steinmetz I, Bartels C. Das Greifswalder Modell der MRSA-Prävention – Maßnahmen zur Kontrolle multiresistenter Erreger [The Greifswald MRSA prevention model – Measures to control multiresistant germs]. Klinikarzt. 2009;38(4):192-6. DOI: 10.1055/s-0029-1223265

[4] Woltering R, Hoffmann G, Daniels-Haardt I, Gastmeier P, Chaberny. MRSA-Prävalenz in medizinischen und pflegerischen Einrichtungen eines Landkreises [Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in patients in long-term care in hospitals, rehabilitation centers and nursing homes of a rural distric in Germany]. Dtsch med Wochenschr. 2008;133(19):999-1003. DOI: 10.1055/s-2008-1075683

[5] Köck R, Brakensiek L, Mellmann A, et al. Cross-border comparison of the admission prevalence and clonal structure of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Hosp Inf. 2009;71(4):320-6. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhin.2008.12.001

[6] Popp W, Hansen D, Kundt R, et al. MRSA-Eintages-Prävalenz als Option für MRSA-Netzwerke. Epidemiol Bull. 2009;38:381. Available from: http://edoc.rki.de/documents/rki_fv/ren4T3cctjHcA/PDF/27BOhS8Pv3dWg_eb38.pdf

[7] Petit C, Dawson A, Biechele J, et al. MRSA-Aufnahme Prävalenz-Screening Saarland 2010. In: 9th Ulmer Symposium Krankenhausinfektionen, 2011 April 12th to 15th, Ulm. Ulm; 2011.

[8] Nationales Referenzzentrum für Surveillance von nosokomialen Infektionen. Modul MRSA-KISS, Referenzdaten – Erstellungsdatum: 26. April 2011. Berlin; 2011. Available from: http://www.nrz-hygiene.de/fileadmin/nrz/module/mrsa/199701_201104_MRSA_reference.pdf

[9] Nationales Referenzzentrum für Surveillance von nosokomialen Infektionen. Modul ITS-KISS, Referenzdaten – Erstellungsdatum: 16.03.2010. Berlin; 2010. Available from: http://www.nrz-hygiene.de/surveillance/kiss/its-kiss/

[10] Geffers C, Gastmeier P. Nosokomiale Infektionen und multiresistente Erreger in Deutschland: Epidemiologische Daten aus dem Krankenhaus-Infektions-Surveillance-System [Nosocomial Infections and Multidrug-Resistant Organisms in Germany-Epidemiological Data From KISS (The Hospital Infection Surveillance System)]. Dtsch Ärztebl Int. 2011;108(6):87-93. DOI: 10.3238/arztebl.2011.0087

[11] Nationales Referenzzentrum für Surveillance von nosokomialen Infektionen. Modul CDAD-KISS, Referenzdaten – Erstellungsdatum: 14. Juni 2011. Berlin; 2011. Available from: http://www.nrz-hygiene.de/fileadmin/nrz/module/cdad/CDADReferenz2010_extern.pdf