Is there a “net generation” in veterinary medicine? A comparative study on the use of the Internet and Web 2.0 by students and the veterinary profession

Christoph Tenhaven 1Andrea Tipold 2

Martin R. Fischer 3

Jan P. Ehlers 1

1 Stiftung Tierärztliche Hochschule Hannover, E-Learning Beratung, Hannover, Deutschland

2 Stiftung Tierärztliche Hochschule Hannover, Klinik für Kleintiere, Hannover, Deutschland

3 Klinikum der LMU München, Lehrstuhl für Didaktik und Ausbildungsforschung in der Medizin, München, Deutschland

Abstract

Introduction: Informal and formal lifelong learning is essential at university and in the workplace. Apart from classical learning techniques, Web 2.0 tools can be used. It is controversial whether there is a so-called net generation amongst people under 30.

Aims: To test the hypothesis that a net generation among students and young veterinarians exists.

Methods: An online survey of students and veterinarians was conducted in the German-speaking countries which was advertised via online media and traditional print media.

Results: 1780 people took part in the survey. Students and veterinarians have different usage patterns regarding social networks (91.9% vs. 69%) and IM (55.9% vs. 24.5%). All tools were predominantly used passively and in private, to a lesser extent also professionally and for studying.

Outlook: The use of Web 2.0 tools is useful, however, teaching information and media skills, preparing codes of conduct for the internet and verification of user generated content is essential.

Keywords

web2.0, social media, veterinary medicine, education, E-Learning, Lifelong Learning, professional training, net-generation, digital natives

Introduction

Every is being encouraged towards lifelong learning (

Although preparation for lifelong learning should take place, as much as possible, while still studying [33], [36], [23], this frequently has not been implemented appropriately [80], [10].

Lifelong learning in medical and veterinary under- and postgraduate education takes many forms [37], [19]. Seminars, lectures, journal articles [40], [57] but also e-learning [21], [30], [29] are amongst the preferred study media.

We distinguish between formal training with certification (CME, ATF) [24]) and informal training (from pure interest or for problem solving) [41], [87]. Likewise, the forms of motivation differ, some study to obtain a certificate or to fulfil the CPD requirements (extrinsic motivation), some from pure interest in the topic (intrinsic motivation) [14], [46].

For some years now, a new generation of learners (Net Generation [87], [25], [76], Generation @ [64], Homo Zappiens [92], [93] or Digital Natives [68], [43]) has been expected by universities, with the assumption that they will prove to be a profound challenge to teaching [75], as they learn and think differently [68].

Other authors take a contrary position, stating there is no empirical basis for grouping together a “net generation” as young people exhibited a much more nuanced usage behaviour and were using modern communication technology not because they exist but to satisfy their own needs [79], [1]. Other authors point out that, despite differences in media habits, personal attitudes and preferences this issue needs to be explored further [12], [52].

Learning and CPD using electronic media in medicine and veterinary medicine has become commonplace and there is great demand for it [30], [56] as it solves various problems which can occur as a result of on-site teaching: seminar costs, travel costs, lack of time or not being able to organise cover at the workplace [22]. Web 2.0 technology is gaining more and more importance for informal learning [66] Web 2.0 refers to internet use which has moved away from mere consumption to so-called prosumption and the technologies necessary for it. This means that users not only obtain information from the internet, but are actively involved in creating, processing and disseminating content [54], [65], [69], [4], [85]. Web 2.0 tools include web forums, social networks, blogs, instant messaging, wikis and podcasts:

- Internet forum: A virtual space on the internet which facilitates discussions and their archiving. The discussion usually does not take place in real time, but asynchronously [28].

- Social network: A social network is defined as a web service where users log on, connect with each other and upload their own content and share with other users of similar primary areas of interest and are able to comment on third-party content [49].

- Blog: A public web diary or journal, also referred to as a web-log [13].

- Instant messaging: Using instant messaging, two or more participants can hold a real-time conversation using text messages via so-called “push function”. An instant messenger (IM) is a computer program which must be installed by all participants of the discussion, the so-called “chat”. A buddy list allows users to see whether users known to them are online and willing to communicate [42].

- Wiki: Software which supports collaborative work on the internet with page content which can be changed by any user via editing the content in their browser and with the further option of engaging in discussion with other users [27], [35].

- Podcasts: Audio and video files which can be subscribed to, usually via an RSS Feed [56].

These Web 2.0 tools are mainly used in veterinary medicine to get quick access to international experts’ opinions and to overcome availability obstacles (e.g. time, distance and cost) [22]. It is said of the above-mentioned net generation that they are particularly keen users of such Web 2.0 tools [87], [68], [93].

Aims

The aim of this study was to determine whether a so-called “net generation” is evident in veterinary medicine. Are there differences in media use, especially of the internet and Web 2.0 media between students of veterinary medicine and the veterinary profession in German-speaking countries? Based on the results, we will draw conclusions about how veterinary medical educational institutions should approach the use of new media.

Methods

To answer this question, an online questionnaire was developed. In addition to personal date, the hardware owned, frequency of internet use and usage patterns in relation to Web 2.0 applications (messaging, blogs, wikis, forums, podcasts, etc.) was queried. In addition, the frequency of internet use via mobile phones was queried, which takes place mainly within this age group.

The questionnaire consisted of 23 multiple choice questions, 15 single choice questions, eight questions with Likert scales (values 1-6, 1=yes, a lot to 6=never) and three free text questions. These questions were part of a larger overall questionnaire on media use in veterinary medicine. Other partial results have already been published elsewhere [11], [55].

The survey was conducted via an online questionnaire on

Statistical analysis was performed directly in the SurveyMonkey questionnaire tool and after downloading the data using the statistical program SPSS 20.0.0 IBM.

Results

1780 participants responded to the questionnaire, of these 1159 were students and 621 veterinarians. At the University of Veterinary Medicine Foundation, the response rate was approximately 27% of all students at this university. Regarding veterinarians and students from other universities, no exact response rate can be determined because we were not able to contact the entire veterinary profession and it is not known whether the students were contacted via the local mailing lists.

The participants were able to skip certain questions or topics, which means that the number of responses per question may vary from the total number of participants. Of the participants, 83.4% were female and 16.6% male.

Internet speed and PC hardware

The majority access the internet via high-speed connections such as DSL (58.1%), university connections (18.1%), cable (5%) and WiFi hotspots (22.5%). 32.1% access the web via mobile devices (WiFi hotspots and UMTS/3G).

Of the respondents, 97.7% are able to play audio files and 97.8% can play video files.

Regarding additional equipment, 88.7% stated they had computer speakers or used built-in speakers, 35.2% use a headset and 36.9% a webcam.

Internet use

Of the respondents, 93.3% use the internet at least once a day and 78.4% use the internet several times a day. Only 0.5% of respondents said they used the internet once a week or less often. There were no significant differences between veterinarians and students, nor between the different age groups.

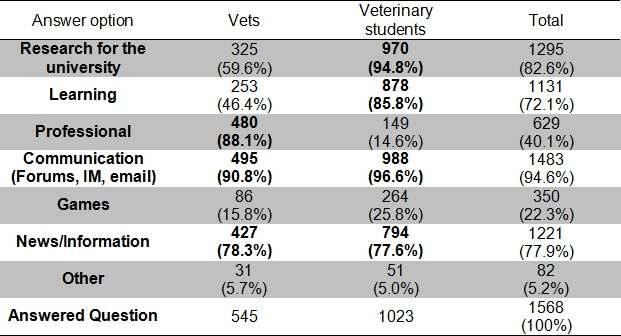

The main reasons for internet use (see Table 1 [Tab. 1]), both amongst the veterinary profession and the students, was “Communication” (in total: 94.6%, 90.8% of vets, 96.6% students) and “News and information” (77.9%/78.3%/77.6%). Otherwise students used the internet mainly for “Research for the university” (94.8%) and “Learning” (85.8%), while veterinarians primarily indicated “Professional” uses (88.1%) .

Social networks

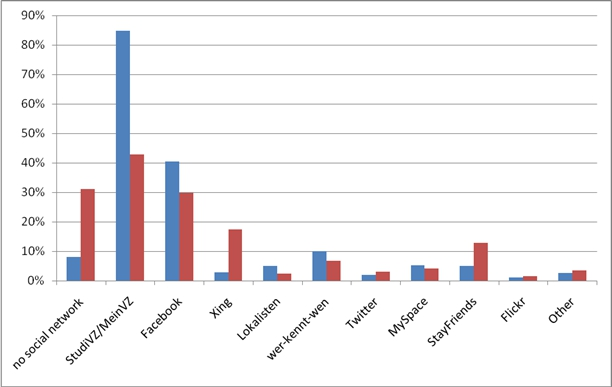

Social networks (see Figure 1 [Fig. 1]) like Facebook and StudiVZ/MeinVZ were used by 84.5% of all respondents, with significant differences between veterinary professionals (69.0%) and students (91.9%). Regular use (at least once per week) was reported by 64.8% (54.1% veterinarians, 82.0% students), 21.5% use social networks several times a day (11.8% veterinarians, 26.6% students). Of the 15.5% of respondents who reported no use of social networks, 1.3% (2.8% veterinarians, 0.5% students) stated they were not aware of social networks.

With 70.2% (42.9% veterinarians, 84.7% students) StudiVZ/MeinVZ is the most widely used social network, followed by Facebook with 36.8% (29.7% veterinarians, 40.5% students). Other social networks are less used.

Internet forums

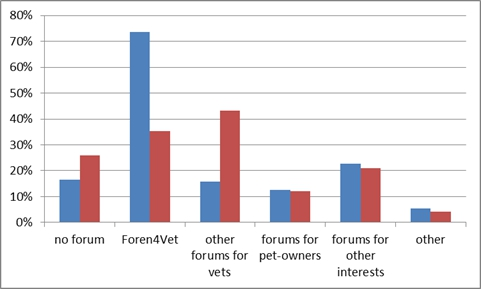

Internet forums (see Figure 2 [Fig. 2]) were used passively regularly by nearly half of all respondents (43.5%). Passive use refers to the plain consumption, in this case reading. A good third of them (16.6% of all respondents) also regularly post on internet forums, i.e. use forums actively. There were no significant differences between students and veterinarians. Use the most widely used internet forum among the respondents who use forums was

Blogs

Regular active (at least once per week) blog use was significantly lower with (3.4%). Active blogging takes place almost exclusively in the private sphere (6.2%). Only 3.2% of respondents stated that they wrote veterinary blogs (1.6%), professional blogs (1.0%) or science blogs (0.6%). Blog use tended to be passive: private blogs (24.3%), veterinary blogs (13.7%), professional blogs (4.1%) and science blogs (7.6%). 8.6% of the respondents responded they were not familiar with blogs, 47.5% had never read a blog and 28.2% did so less often than once a week. Here too, no significant differences between students and veterinarians were found.

Wikis

The difference was even more evident in the active and passive use of wikis such as Wikipedia (see Figure 3 [Fig. 3] and 4 [Fig. 4]). 52.5% indicated they regularly used wikis for research. In contrast, 1% said they regularly wrote or corrected contributions. No significant differences between veterinarians and students were found.

The most widely used wiki was Wikipedia (95.6%). The most widely used veterinary wikis were vetipedia (11.9%) and wikivet (8.2%). 2% of all respondents used other non-veterinary wikis apart from Wikipedia.

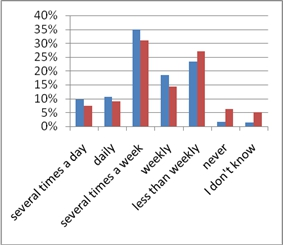

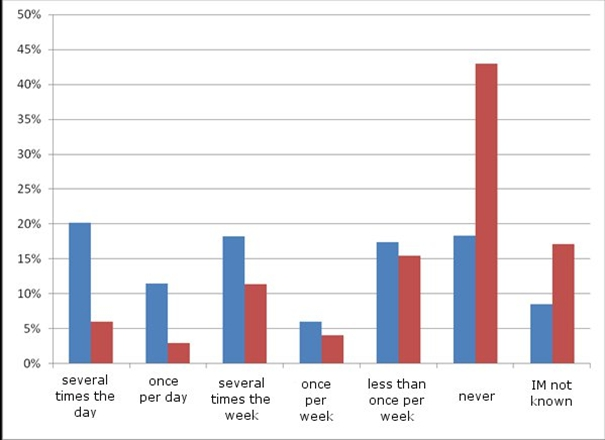

Instant messaging

Of all respondents, 45% (24.5% veterinarians, 55.9% students) used instant messaging (IM) (see Figure 5 [Fig. 5]) regularly (once per week or more often). In contrast, 26.8% (43.0% veterinarians, 18.3% students) never used IM and 11.5% (17.1% veterinarians, 8.3% students) did not know what IM was. Particularly noticeable was that amongst those using IM several times a day, the veterinary profession was less well represented (6%) than students (20.2%).

With 45.6% (36.8% veterinarians, 50.2% students), Skype was the most widely used messenger, followed by ICQ with 33.9% (14.8% veterinarians, 43.8% students) and Windows Live Messenger with 13.6% (7.8% veterinarians, 16.7% students). The chat tool of social networking sites that had a similar function were also queried. 12% (8.3% veterinarians, 13.9% students) of respondents reported using them. 32.9% (50.7% veterinarians, 23.7% students) of all respondents used no form of instant messaging.

Podcasts and video podcasts

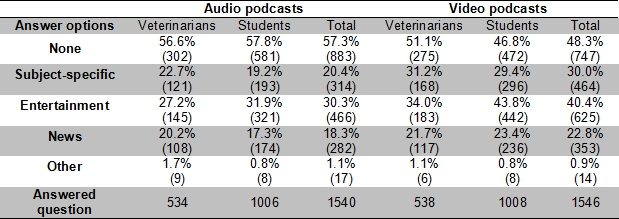

Hardly any podcasts and video podcasts (see Table 2 [Tab. 2]) are created actively (podcasts by 1.7% and video podcasts by 2.1% of all respondents). Here veterinarians are more active than students (3.7% veterinarians, 1.2% students).

Passive use is higher (15.5% audio podcasts, 20.2% video podcasts) and is approximately the same in both groups. Subject-specific (20.4%), news (18.3%) and entertainment podcasts (30.3%) were frequented.

The ratio for video podcasts is similar: subject-specific (30.0%), news (22.8%) and entertainment podcasts (40.4%). Regarding the use of podcasts and video podcasts, there are no significant differences between veterinarians and students.

Mobile phone use

Mobile phones are primarily used for making phone calls both by veterinarians and students alike (97.1%: 97.4% veterinarians, 96.9% students) and text messaging (91.8%: 85.2% veterinarians, 95.4% students). 43.3% (34.4% among veterinarians - Students 48.1%) used their mobile phones for taking pictures, 21% (14.5% veterinarians, 24.4% students) for listening to music while using the internet (6.7%: 7.7% veterinarians, 6.1% students) and writing and receiving emails (5%: 7.7% veterinarians, 3.5% students) was a less commonly used feature.

Discussion

Finding a means of carrying out as comprehensive a survey as possible was needed which could reach all relevant target groups in order to be able to assess the equipment, internet speed and usage in the veterinary profession and amongst the students of veterinary medicine. This study chose an online survey because in terms of reliability and validity they compare well with traditional surveys [5], [47], [50]. Online questionnaires also have the advantage that the interviewer cannot exert any influence on the respondents and that the respondent remain anonymous, thus possibly eliciting more honest answers [58], [6].

The high number of participants in the survey included all occupational groups of veterinary medicine and provides useful results even if university staff and students were over-represented in comparison to the total veterinary profession [15]. The gender distribution of the sample was approximately equivalent to the distribution in the student body and amongst veterinarians [15].

Multiple participation in the survey is rather unlikely [9] but would not have led to any bias in the results [83].

The response rate for veterinarians and students of all universities, except for the University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover, could not be determined because it is unknown how many veterinarians and students were reached. This is one of the major problems with internet surveys [91]. Only the number of answered questionnaires can be counted, as click counters are also not good indicators [51]. In contrast, determining the response rate of students of the School of Veterinary Medicine Foundation was possible since they were contacted via the mailing lists for each semester, so each student received an invitation to the survey. The response rate among students of the School of Veterinary Medicine Hannover was comparable with the response rate of an online survey of students in Michigan in 2001 following the first invitation by email [20] although the students at the University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover received only one invitation via the semester mailing list. For written surveys, a response rate of 5 - 30% can be expected [58]. In general, a survey fatigue trend over the last decades can be observed [78].

PC hardware and internet use

The study paid special attention to hardware configuration in terms of audio and video because the School of Veterinary Medicine Hannover has plans to increase the use of podcasts, and videos. We found that almost all respondents were able to quickly download and play this type of media. The computer equipment in the veterinary field was therefore above the national average [

PC and internet are an indispensable tool for the majority of students [44] and the web has become a part of medical education in many ways [45]. Nevertheless, the main motivations for using the internet identified in this study lie in the private sphere, even if a majority of respondents also use the internet for degree courses or professionally for research and learning. A survey of children and adolescents in Germany showed that their motivations are primarily communication (social networks, email and instant messaging), multimedia (video portals, music and video downloads), news and information (search engines, information pages and wikis) and research for school (working on the web with a computer at home and at school) [8], [7].

What points to a net generation in veterinary medicine?

Instant messaging and social networks are used more and more frequently by students. This differential use of social networks was also described by Sandars and Schroter [77]. Roblyer et al. [73] see this as an opportunity for teaching in the future. Nationally, most users of social networks are in the 14-29 age group, followed by those aged 30-49 [8], [7], [90]. This corresponds exactly to the age groups of students and university staff. But social networks are currently still used mainly privately [66]. Another snapshot of social networks in higher education shows that they have not yet been used for teaching purposes but further studies are necessary to determine suitability for professional exchange and teaching [73]. Initial studies in this field have been initiated in veterinary medicine [3]. But this makes training for students and teachers in Web 2.0 indispensable [77], as these studies have shown (see below). In addition, universities should design codes of conduct for staff and students who often are members of social networks [53]. But there are also concerns about integrating teaching into social networks and networking of teachers and students such as negative remarks (flaming), private photos (bullying), data protection and so on [60]. It may be wise for some individuals to separate personal and professional accounts [88].

The differences in the use of instant messaging between the age groups under and over 30 found in this study have also been noticed elsewhere [32], [77], [8], [7]. This suggests that communication can be switched to IM and that appointments with students, for example, could be held online. International meetings, courses and CPD could be prepared, held and followed up via IM or virtual classrooms [55], [22] Students see instant messaging as a good addition to teaching for the future [74].

What points away from a net generation in veterinary medicine?

As described in detail by Schulmeister [79], the concept of a generation is hard to grasp and not clearly defined [18].

New studies assume that students do not learn differently than their predecessors [61]. However, the computer is a central tool for obtaining information [17].

The use of internet forums, blogs, wikis, podcasts and mobile phones does not differ to such an extent between the two groups studied here to claim more intensive use them by one of the two groups. The utilization rates of Web 2.0 media are high. Passive (consuming) use predominated, as opposed to active (producing) use. Sandars and Schroter [77] have already called for an increased use of Web 2.0 for medical students, something which should also be expanded and trained in veterinary medicine.

It is striking in the present study that podcasts (audio and video) are consumed primarily for entertainment but also for obtaining subject-specific information and news. Podcasts, blogs and wikis can used effectively to encourage learning and communication between doctors, students and patients [13]. Codes of conduct for the use of Web 2.0 tools are required, so that no unprofessional content is provided in connection with online teaching [16].

In order to ensure that student-generated content (cf “user generated content”) is of sufficient academic rigour, methods must be developed to verify such content [39]. But the use of Web 2.0 must also be encouraged amongst the teaching staff, which will require further research into teaching [26].

With rapid growth of smart phones on the mobile phone market [

Conclusions

Based on the collected data, it is not possible to prove the existence of a uniform “net generation” in veterinary medicine. For almost all respondents use of the web is natural irrespective of age differences. There are differences in the usage of social networks and instant messaging. Other Web 2.0 tools were used equally, with considerably more data being consumed than produced, more commonly in private than in professionally.

Students of veterinary medicine and veterinarians are comparable with other professional groups in terms of their usage.

It is therefore important to train both teachers and students (i.e. students, teaching staff and veterinarians) in the used of media and to illustrate both risks and opportunities. In addition, web policies regarding professional conduct on the web in general and especially on social networks should be created and further research carried out on this topic.

We see information and media competence as a key skill which enables evidence-based lifelong learning and thus as core competency for students and veterinarians.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks go to Volkswagenstiftung und Gesellschaft der Freunde der TiHo for supporting this study.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

[1] Arnold P. Die "Netzgeneration" - Empirische Untersuchungen zur Mediennutzung bei Jugendlichen. In: Schön S, Ebner M (Hrsg). Lehrbuch für Lernen und Lehren mit Technologien. Graz: TU Graz, L3T; 2011.[2] Babalobi OO. Towards a development and use of internet web and information communication technologies for veterinary medicine education in Nigeria. 5th Conference of animal health information specialists. Onderstepoort: University of Pretoria; 2007.

[3] Baillie S, Kinnison T, Forrest N, Dale VH, Ehlers JP, Koch M, Mándoki M, Ciobotaru E, de Groot E, Boerboom TB, van Beukelen P. Developing an Online Professional Network for Veterinary Education: The NOVICE Project. J Vet Med Educ. 2011;38(4):395-403. DOI: 10.3138/jvme.38.4.395

[4] Bartolomé A. Web 2.0 and New Learning Paradigms. eLearn Paper. 2008;8:4. Zugänglich unter/available from: http://www.elearningeuropa.info/files/media/media15529.pdf

[5] Batinic B. Fragebogenuntersuchungen im Internet. Aachen: Shaker-Verlag; 2001.

[6] Baur N, Florian MJ. Stichprobenprobleme bei Online-Umfragen. In: Jakob N, Schoen H, Zerback T (Hrsg). Sozialforschung im Internet. Methodologie und Praxis der Onlien-Befragung. Wiesbaden: VS-Verlag; 2008. S.109-128.

[7] Behrens P, Rathgeb T. Jugend, Information, (Multi-) Media; Basisstudie zum Medienumgang 12- bis 19-Jähriger in Deutschland. Stuttgart: Medienpädagogischer Forschungsverbund Südwest; 2011. Zugänglich unter/avialable from: http://www.mpfs.de/fileadmin/JIM-pdf11/JIM2011.pdf

[8] Behrens P, Rathgeb T. Kinder + Medien, Computer + Internet; Basisuntersuchung zum Medienumgang 6- bis 13-Jähriger in Deutschland. Stuttgart: Medienpädagogischer Forschungsverbund Südwest; 2010. Zugänglich unter/available from: http://www.mpfs.de/fileadmin/KIM-pdf10/KIM2010.pdf

[9] Birnbaum MH. Human Research and Data Collection via the Internet. Ann Rev Psychol. 2004;55(1):803-832. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141601

[10] Blumberg P. Why Self-Directed Learning Is Not Learned and Practiced in Veterinary Education. J Vet Med Educ. 2005;32(3):290-295.

[11] Börchers M, Tipold A, Pfarrer C, Fischer MR, Ehlers JP. Akzeptanz von fallbasiertem, interaktivem eLearning in der Tiermedizin am Beispiel des CASUS-Systems. Tierärztl Prax Ausg K Kleintiere Heimtiere. 2010;38(6):379-388.

[12] Borges NJ, Manuel RS, Elam CL, Jones BJ. Comparing Millennial and Generation X Medical Students at One Medical School. Acad Med. 2006;81(6):571-576. DOI: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000225222.38078.47

[13] Boulos M, Maramba I, Wheeler S. Wikis, blogs and podcasts: a new generation of Web-based tools for virtual collaborative clinical practice and education. BMC Med Educ. 2006;6(1):41. DOI: 10.1186/1472-6920-6-41

[14] Brigley S. Continuing education in the medical professions: professional development or bureaucratic convenience? Teach Develop. 1997;1(2):175-190. DOI: 10.1080/13664539700200022

[15] Bundestierärztekammer. Statistik 2009: Tierärzteschaft in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Dtsch Tierärztebl. 2010:4.

[16] Chretien KC, Greysen SR, Chretien JP, Kind T. Online Posting of Unprofessional Content by Medical Students. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1309-1315. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2009.1387

[17] Conole G, de LaatM, Dillon T, Darby J. "Disruptive technologies", "pedagogical innovation": What's new? Findings from an in-depth study of students' use and perception of technology. Comp Educ. 2008;50(2):511-524. Zugänglich unter/available from: http://www.e4innovation.com/Papers/conole_lxp_cal_paper%20v2.pdf

[18] Corsten M. Generation und institutioneller Wandel. SFB 580 Mitteil. 2003;9:83-89.

[19] Costa SD. Medizinische Aus-, Weiter- und Fortbildung: Versuchte Definitionen - Medical Training and Residency Programs: Current Caveats. Geburtshilf Frauenheilkund. 2009;69(12):1065-1070. DOI: 10.1055/s-0029-1240646

[20] Couper MP. Web Survey Design and Administration. Public Opin Q. 2001;65(2):230-253. DOI: 10.1086/322199

[21] Curran VR, Fleet L. A review of evaluation outcomes of web-based continuing medical education. Med Educ. 2005;39(6):561-567. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02173.x

[22] Dale VH, Kinnison T, Short N, May SA, Baillie S. Web 2.0 and the veterinary profession: current trends and future implications for lifelong learning. Vet Rec. 2011;169(18):467. DOI: 10.1136/vr.d4897

[23] Dale VH, Sullivan M, May SA. Adult Learning in Veterinary Education: Theory to Practice. J Vet Med Educ. 2008;35(4):581-588. DOI: 10.3138/jvme.35.4.581

[24] Davis D, O'Brien MA, Freemantle N, Wolf FM, Mazmanian P, Taylor-Vaisey A. Impact of Formal Continuing Medical Education. JAMA. 1999;282(9):867-874. DOI: 10.1001/jama.282.9.867

[25] De Witt C. Medienbildung für die Netz-Generation. Medien Pädag. 2000;1(1):1-12.

[26] Doherty I, Cooper P. Educating educators in the purposeful use of Web 2.0 tools for teaching and learning. Auckland: University of Auckland; 2009. S.208-217. Zugänglich unter: http://www.ascilite.org.au/conferences/auckland09/procs/doherty.pdf

[27] Ebersbach A, Glaser M, Heigl R, Warta A. Wiki - Kooperation im Web. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2007.

[28] Ebner M. Internetforen: verwenden - einrichten – betreiben. Norderstedt: Books on Demand; 2008.

[29] Ehlers JP, Ehlers S, Behr M, Kähn W, Bollwein H, Leidl W. OnLineLectures - eLearning als Ergänzung der tierärztlichen Fortbildung. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2008;25(4):Doc101. Zugänglich unter/available from: http://www.egms.de/static/de/journals/zma/2008-25/zma000586.shtml

[30] Ehlers JP, Wittenberg B, Fehrlage K, Neumann S. VETlife - continuing veterinary education arranged by eLearning. ECEL 2007 - 6th European Conference on e-Learning; 4-5 October 2007; Copenhagen, Denmark. Reading: Academic Conferences Ltd; 2007. S.183-187. Zugänglich unter/available from: http://www.academic-conferences.org/pdfs/ecel07-booklet.pdf

[31] Fick J, Doluschitz R. Vernetzung tiergesundheitsrelevanter Daten zu einem integrierten Tiergesundheitssystem. Züchtungskunde. 2007;80(1):11-19.

[32] Finkenhagen K, Haga Ø. How can Instant Messaging support communication in a Wireless Environment? – Medical Students use of Personal Digital Assistant for Messaging in the Knowmobile Project. Oslo: University of Oslo, Department of Informatics; 2002.

[33] Fox RD, West RF. Developing medical student competence in lifelong learning: the contract learning approach. Med Educ. 1983;17(4):247–253. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1983.tb01458.x

[34] Frankford DM, Patterson MA, Konrad TR. Transforming Practice Organizations to Foster Lifelong Learning and Commitment to Medical Professionalism. Acad Med. 2000;75(7):708-717. DOI: 10.1097/00001888-200007000-00012

[35] Franklin T, van Harmelen M. Web 2.0 for Content for Learning and Teaching in Higher Education. London: The Observatory of Borderless Higher Education; 2007. Zugänglich unter/available from: http://190.208.26.22/files/web2-content-learning-and-teaching.pdf

[36] Genn JM. Curriculum, environment, climate, quality and change in medical education—a unifying perspective. Med Teach. 2001;23(4):337-344. DOI: 10.1080/01421590120063330

[37] Gerlach FM, Beyer M. Ärztliche Fortbildung aus der Sicht niedergelassener Ärztinnen und Ärzte – repräsentative Ergebnisse aus Bremen und Sachsen-Anhalt. Z Arztl Fortbild Qual Gesundheitswes. 1999;93:581–589.

[38] Goldfinger SE. Continuing Medical Education – The Case for Contamination. New Engl J Med. 1982;306:540-541. DOI: 10.1056/NEJM198203043060910

[39] Gray K, Thompson C, Sheard J, Clerehan R, Hamilton M. Students as Web 2.0 authors: Implications for assessment design and conduct. Aus J Educ Technol. 2010;26(1):105-122. Zugänglich unter/available from: http://www.ascilite.org.au/ajet/ajet26/gray.pdf

[40] Griebenow R, Lehmacher W, Lösche P, Krämer L, Niesen S, Lee J, Christ H, Stützer H, Stosch C. Evaluation of continuing medical education (CME) in print media. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2003;128(14):725-733. DOI: 10.1055/s-2003-38422

[41] Grzybowski S, Lirenman D, White MI. Identifying educational influentials for formal and informal continuing medical education in the province of British Columbia. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 20002;20(2):85-90.

[42] Guernsey L. Message to Marketers: RU4 Real? New York: The New York Times; 2001.

[43] Günther J. Digital Natives & Digital Immigrants. Innsbruck, Wien, Bozen: Studienverlag; 2007.

[44] Hanekop H. PC- und Internetnutzung im Studium aus der Sicht der Studierenden. PIK. 2003;26(3):125-132. DOI: 10.1515/PIKO.2003.125

[45] Harden RM. Trends and the future of postgraduate medical education. Emer Med J. 2006;23(10):798-802. DOI: 10.1136/emj.2005.033738

[46] Heath KJ, Jones JG. Experiences and attitudes of consultant and nontraining grade anaesthetists to continuing medical education (CME). Anaesth. 1998;53(5):461-467. DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.1998.00373.x

[47] Hertel G, Naumann S, Konrad U, Batinic B. Person assessment via Internet: comparing Online and paper-and-pencil questionnaires. In: Batinic B, Reips UD, Bosnjuak M (Hrsg). Online Social Sciences. Seattle, WA: Hogrefe & Huber; 2002.

[48] Hoblet KH, Maccabe AT, Heider LE. Veterinarians in Population Health and Public Practice: Meeting Critical National Needs. J Vet Med Educ. 2002;30(3):232-239.

[49] Kamel Boulos MN, Wheeler S. The emerging Web 2.0 social software: an enabling suite of sociable technologies in health and health care education. Health Inform Libr J. 2007;24(1):2-23. DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2007.00701.x

[50] Kaplowitz MD, Hadlock TD, Levine R. A Comparison of Web and Mail Survey Response Rates. Public Opin Q. 2004;68(1):94-101. DOI: 10.1093/poq/nfh006

[51] Kaye BK, Johnson TJ. Research Methodology: Taming the Cyber Frontier. Soc Sci Comp Rev. 1999;17(3):323-337. DOI: 10.1177/089443939901700307

[52] Kennedy G, Dalgarno B, Gray K, Judd T, Waycott J, Bennet S, Maton K, Krause K, Bishop A, Chang R, Churchwood A. The net-generation are not big users of Web 2.0 technologies: Preliminary findings from a large cross-institutional study. Singapore: Nanyang Technological University Press, Centre for Educational Development; 2007. Zugänglich unter/available from: http://www.ascilite.org.au/conferences/singapore07/procs/kennedy.pdf

[53] Kind T, Genrich G, Sodhi A, Chretien KC. Social media policies at US medical schools. Med Educ Online. 2010;15:15. DOI: 10.3402/meo.v15i0.5324

[54] Knorr E. The Year of Web Services. IT Magazine CIO. 2003;90.

[55] Koch M, Fischer MR, Tipold A, Ehlers JP. Can Online-Conference systems improve veterinary communication. AMEE 2010 Conference, Glasgow (UK), 04.-08.09.2010. Dundee (UK): AMEE; 2010. S.115

[56] Konrad MH. Mobile Learning mit podcasts. Anaesth. 2009;58(6):633-635. DOI: 10.1007/s00101-009-1557-5

[57] Kühne-Eversmann L, Nussbaum C, Reincke M, Fischer MR. CME-Fortbildungsangebote in medizinischen Fachzeitschriften: Strukturqualität der MC-Fragen als Erfolgskontrollen. Med Klinik (Munich). 2007;102(12):993-1001. DOI: 10.1007/s00063-007-1123-3

[58] Kutsch HB. Repräsentativität in der Online-Marktforschung. Lohmar, Köln: Josef Eul Verlag GmbH; 2007.

[59] Lenhart A, Purcell K, Smith A, Zickuhr K. Social Media & Mobile Internet Use Among Teens and Young Adults. Washington D.C.: Pew Research Center; 2010. Zugänglich unter/avialable from: http://pewresearch.org/pubs/1484/social-media-mobile-internet-use-teens-millennials-fewer-blog

[60] Maranto G. Barton M. Paradox and Promise: MySpace, Facebook, and the Sociopolitics of Social Networking in the Writing Classroom. Comp Composition. 2010;27(1):36-47. DOI: 10.1016/j.compcom.2009.11.003

[61] Margaryan A, Littlejohn A. Are digital natives a myth or reality? University students' use of digital technologies. Comp Educ. 2011;56(2):429-440. Zugänglich unter/available from: http://www.academy.gcal.ac.uk/anoush/documents/DigitalNativesMythOrReality-MargaryanAndLittlejohn-draft-111208.pdf

[62] Masters K. For what purpose and reasons do doctors use the Internet: A systematic review. Int J Med Inform. 2008;77(1):4-16. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2006.10.002

[63] Merkur S, Mladovsky P, Mossialos E, McKee M. Do lifelong learning and revalidation ensure that physicians are fit to practise? Copenhagen (DK): WHO Eurpean Ministerial Conference on Health Systems; 2008. Zugänglich unter/avialable from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/75434/E93412.pdf

[64] Opaschowski HW. Generation @. Die Medienrevolution entlässt ihre Kinder: Leben im Informationszeitalter. Hamburg, Ostfildern: Kurt Mair Verlag; 1999.

[65] O'Reilly T. Web 2.0 Compact Definition: Trying Again. Sebastopol: O'Reilly; 2006. Zugänglich unter/avialable from: http://radar.oreilly.com/2006/12/web-20-compact-definition-tryi.html

[66] Overwien B. Stichwort: Informelles lernen. Z Erziehungswiss. 2005;8(3):339-355. DOI: 10.1007/s11618-005-0144-z

[67] Pempek TA, Yermolayeva, YA, Calvert SL. College students' social networking experiences on Facebook. J App Dev Psychol. 2009;30(3):227-238. DOI: 10.1016/j.appdev.2008.12.010

[68] Prensky M. Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants Part 1. Horizon. 2001;9(5):1-6. DOI: 10.1108/10748120110424816

[69] Prinz W. Web 2.0 - Bedeutung, Chancen und Risiken. E-Interview mit Prof. Wolfgang Prinz zum Virtual Roundtable "Web Competence & Responsibility" Teil1. München: Fraunhofer FIT; 2007.

[70] Ramsey PG, Carline JD, Inui TS, Larson EB, LoGerfo JP, Norcini JJ, Wenrich MD. Changes over time in the knowledge base of practicing internists. JAMA. 1991;266(8):1103–1107. DOI: 10.1001/jama.1991.03470080073032

[71] Rancich AM, Pérez ML, Morales C, Gelpi RJ. Beneficence, justice, and lifelong learning expressed in medical oaths. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2005;25(3):211-220. DOI: 10.1002/chp.32

[72] Rat der Europäischen Union. Bericht des Rates (Bildung) an den Europäischen Rat über die konkreten künftigen Ziele der Systeme der allgemeinen und beruflichen Bildung, 5980/01 EDUC 23. Brüssel: Rat der Europäischen Union; 2001.

[73] Roblyer MD, McDaniel M, Webb M, Herman J, Witty JV. Findings on Facebook in higher education: A comparison of college faculty and student uses and perceptions of social networking sites. Int High Educ. 2010;13(3):134-140. DOI: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2010.03.002

[74] Rogozea L, Miclaus R, Nemet C, Balescu A, Moleavin I. Education, ethics and e-Communication in medicine. In: Zamanillo Sáinz de la Maza JM, López Espi PL (Hrsg). Proceedings of the 8th WSEAS international conference on Distance learning and web engineering. Wisconsin/USA: World Scientific and Engineering Academy and Society (WSEAS); 2008.

[75] Sandars J, Homer M. Reflective learning and the Net Generation. Med Teach. 2008;30(9-10):877-879. DOI: 10.1080/01421590802263490

[76] Sandars J, Morrison C. What is the Net Generation? The challenge for future medical education. Med Teach. 2007;29(2-3):85-88. DOI: 10.1080/01421590601176380

[77] Sandars J, Schroter S. Web 2.0 technologies for undergraduate and postgraduate medical education: an online survey. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83(986):759-762. DOI: 10.1136/pgmj.2007.063123

[78] Sax LJ, Gilmartin SK, Bryant AN. Assessing Response Rates and Nonresponse Bias in Web and Paper Surveys. Res High Educ. 2003;44(4):409-432. Zugänglich unter/available from: http://illume.arizona.edu/sites/illume.arizona.edu/files/nonrespbiast.pdf

[79] Schulmeister R. Gibt es eine Net-Generation? Hamburg: Universität Hamburg; 2009.

[80] Shaughnessy AF, Slawson DC. Are we providing doctors with the training and tools for lifelong learning? BMJ. 1999;319(7220):1280. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.319.7220.1280

[81] Shekelle PG, Ortiz E, Rhodes S, Morton SC, Eccles MP, Grimshaw JM, Woolf SH. Validity of the Agency for Healthcare Research and quality clinical practice guidelines: how quickly do guidelines become outdated? JAMA. 2001;286(12):1461–1467. DOI: 10.1001/jama.286.12.1461

[82] Shin DH, Shin YJ, Choo H, Beom K. Smartphones as smart pedagogical tools: Implications for smartphones as u-learning devices. Comp Human Beh. 2011;27(6):2207-2214. DOI: 10.1016/j.chb.2011.06.017

[83] Srivastava S, John OP, Gosling SD, Potter J. Development of personality in early and middle adulthood: Set like plaster or persistent change? J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84(5):1041-1053. DOI: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.5.1041

[84] Stark B. Konstanten und Veränderungen der Mediennutzung in Österreich - Empirische Befunde aus den Media-Analyse-Daten (1996 –2007). SWS-Rundschau. 2009;49(2):130-153.

[85] Straub R. Is the world open? eLearn Paper. 2008;8:3.

[86] Swanwick T. Informal learning in postgraduate medical education: from cognitivism to 'culturism'. Med Educ. 2005;39(8):859-865. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02224.x

[87] Tapscott D. Growing Up Digital: The Rise of the Net Generation. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1997.

[88] Thompson L, Dawson K, Ferdig R, Black EW, Boyer J, Coutts J, Black NP. The Intersection of Online Social Networking with Medical Professionalism. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):954-957. DOI: 10.1007/s11606-008-0538-8

[89] TKNDS. Berufsordnung der Tierärztekammer Niedersachsen Körperschaft des öffentlichen Rechts. Dtsch Tierärztebl. 2011;7:949.

[90] Van Eimeren B, Frees B. Drei von vier Deutschen im Netz – ein Ende des digitalen Grabens in Sicht? Med Persp. 2011;7(8):334-349.

[91] Van Selm M, Jankowski N. Conducting Online Surveys. Qual Quant. 2006;40(3):435-456. DOI: 10.1007/s11135-005-8081-8

[92] Veen W. A new force for change: Homo Zappiens. Learn Cit. 2003;(7):5-7.

[93] Veen W, Vrakking B. Homo Zappiens: Growing Up in a Digital Age. Network: Educ Pr Ltd; 2006.