Science Translational Medicine – improving human health care worldwide by providing an interdisciplinary forum for idea exchange between basic scientists and clinical research practitioners

Katherine Forsythe 11 American Association for the Advancement of Science, Washington D.C., USA

Abstract

Science Translational Medicine’s

The journal features peer-reviewed research articles, perspectives and commentary, and is guided by an international Advisory Board, led by Chief Scientific Adviser, Elias A. Zerhouni, M.D., former Director of the National Institutes of Health, and Senior Scientific Adviser, Elazer R. Edelman, M.D., Ph.D., Thomas D. and Virginia W. Cabot Professor of Health Sciences and Technology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The Science Translational Medicine editorial team is led by Katrina L. Kelner, Ph.D., AAAS.

A profound transition is required for the science of translational medicine. Despite 50 years of advances in our fundamental understanding of human biology and the emergence of powerful new technologies, the rapid transformation of this knowledge into effective health measures is not keeping pace with the challenges of global health care. Creative experimental approaches, novel technologies, and new ways of conducting scientific explorations at the interface of established and emerging disciplines are now required to an unprecedented degree if real progress is to be made. To aid in this reinvention, Science and AAAS have created a new interdisciplinary journal, Science Translational Medicine.

The following interview exemplefies the pioneering content found in Science Translational Medicine. It is an excerpt from a Podcast interview

Dr. Broder’s perspective marks the 25th anniversary of modern antiretroviral drug discovery and development. In the early 1980s, Dr. Broder’s research team adapted the nucleotide analog AZT for treating HIV infection, thus ushering in the era of antiretroviral therapies that have enabled HIV-positive individuals to live longer. The Podcast interview was conducted by Annalisa VanHook, Associate Online Editor, AAAS.

Keywords

Science Translational Medicine, basic research, translational research, clinical research, emerging disciplines, interdisciplinary, human biology, AIDS, HIV, HTLV, disease, retroviruses, antiretroviral therapies, AZT, National Cancer Institute, immunodeficiency, cancer, translational medicine, pharmaceutical, new paradigms in medicine

Twenty-five years of translational medicine in antiretroviral therapy: promises to keep

Interviewer – Annalisa VanHook: Before HIV was identified as the causative agent of AIDS, and before HTLV-1 was identified as the causative agent of a subset of T cell lymphomas, researchers didn’t seem to think it was likely that retroviruses would cause disease in humans. And even once HIV and HTLV were identified as causing disease, then people seemed to think that it might be futile to try and treat these retroviruses. Why was that idea prevalent in the scientific community?

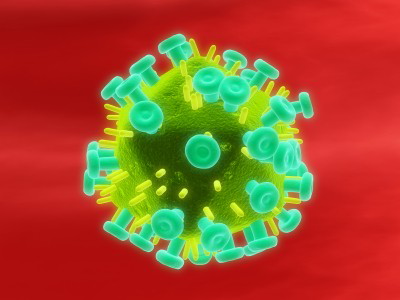

Interviewee – Dr. Samuel Broder: The existence of animal retroviruses – that is, RNA viruses that replicate by reverse transcriptase – was already well known and widely accepted. But, there was a widespread belief that activating – that means replicating retroviruses – did not exist in human beings, partially because there had been an extensive search for them that was entirely negative. Then there was a secondary belief that even if human retroviruses did exist, they were not really involved in the pathogenesis of major human diseases. While there were some exceptions – you mentioned HTLV-1 as a cause of certain subacute T cell leukemias or, in some cases, tropical spastic paraparesis – many people felt that they, at most, played a minor role in the general public health. And then, when it was discovered and formally proven, by Gallo and Montagnier, that retroviruses really were the principle causative agent for AIDS, there was a sense of futility because it was felt that retroviruses, by their very nature, were inherently untreatable (Figure 1 [Fig. 1]). This is for two reasons: They had a capacity to integrate into DNA of the host, and they could rapidly mutate due to the error-prone reverse transcriptase that they possessed, and both of those factors were felt to be essentially impossible barriers to the development of effective antiretroviral therapy. So, I think that was the feeling, that was the prevailing mood that we faced in 1984 when we began thinking very seriously about trying to develop antiretroviral agents, of which the first that went through our pipeline into human beings was AZT. That was done in a collaboration of what was then called the Burroughs-Wellcome Company and also academic investigators at Duke University.

Figure 1: Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a member of the retrovirus family that causes acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). [Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/Sebastian Kaulitzki]

AV: The time in between when HIV was identified as the causative agent of AIDS and the identification of the nucleotide analogs as potentially useful antiviral drugs, and then finally the human trials and approval of AZT and getting AZT into the clinic took only about two years ...

SB: It probably ranks among the most rapid timelines in modern pharmaceutical history. And I think it was a number of factors that made that possible. But, it is something that we were very fortunate to achieve.

AV: What was there about the emergence of HIV and AIDS that enabled that – that made that happen so quickly?

SB: AIDS, at the time, initially was an extremely mysterious disease, and it had appalling consequences. And it was associated with an enormous deterioration of the immune response, the onset of certain kinds of neoplasms, of which Kaposi’s sarcoma is one, and it had a rapidly fatal outcome. It particularly also struck individuals in the prime of life, young individuals, and that, in turn, added an extra dimension of urgency. But, I think one of the things I want to just stress is the environment, or culture, in which a research program exists, is immensely important to this kind of discussion. I was very lucky to be part of the National Cancer Institute Intramural Program, and I think the location of my group within the Intramural Program of the National Cancer Institute had very special benefits for this antiretroviral drug discovery and development. And to add to that, the NCI, at the time, placed a very high priority on novel drug development and had considerable expertise in the clinical pharmacology and toxicology. And then the leadership at NCI at the time endorsed the philosophy that really is based on what Arthur C. Clarke has said, illustrating what it takes to break paradigms. And that is, the leadership at NCI endorsed the philosophy that, in order to discover the limits of what you think is possible, you sometimes have to go a little way past them into the territory of the impossible, and the boundaries constantly shift, in any case. But, if you’re totally afraid of crossing into the line of what might be impossible, if you’re very fearful that that will make you somehow look bad or that you’ll look foolish or something, you can’t really make major advances, in my opinion. And the NCI really strongly supported translational medicine, although that term was not in use at the time.

AV: In your Perspective, you mention the need to adopt new paradigms for funding and for expediting the process of developing treatments and getting them into patients. And specifically, you mentioned the need for collaboration between the public and the private sectors. Why is neither sector ideally suited to successfully manage these large studies on their own, and how would the collaboration of the two be able to improve translational efforts?

SB: It isn’t merely the large studies that we’re talking about – that’s part of the equation – but actually there’s a larger issue. I think that certain types of drug discovery and certain types of drug development can be done in the private sector extremely well, but the private sector cannot undertake certain types of basic research or translational research when there is a significant chance of failure and when many of the assumptions are not proven. And so, it becomes very difficult to take on certain types of very far-reaching, paradigm-shifting experiments and to move them into the clinic and to move them to registration. That requires collaboration with the academic community and with the Intramural Program of the National Institutes of Health. So, a translational medicine approach, in which the probability of success or time to completion can’t be precisely quantified, would be beyond the reach of many drug development programs – quite frankly, either private or publicly funded. The other thing that I want to stress is that we need to have a wholeness of motion between the lab and the clinic. I think a compartmentalization –in which people do discovery in the lab and then almost like a relay race, turn it over to people in the clinic who are possibly in a different administrative structure or geographic location – can work, but it does not really take the best advantage of what translational medicine means, in my opinion. So, we need to restore and replenish the notion of the wholeness of motion where clinical investigators can actually do basic research and vice versa. And I think that that is becoming more and more difficult. Think there is a specialization – it’s an understandable specialization – but I think it would be important to have as many opportunities to fund, support, and train individuals who can do this wholeness of motion – that is, moving from the lab to the clinic and vice versa, from the clinic back to the lab.

Read the full transcript of the Podcast: http://stm.sciencemag.org/content/suppl/2010/07/05/2.39.39pc5.DC1/ScienceTranslMed_100707.pdf

References

[1] Science Translational Medicine. Washington, DC: American Association for the Advancement of Science. Available from: http://stm.sciencemag.org[2] Broder S, VanHook A. [Podcast: 7 July 2010]. Washington, DC: Sci Trans Med; 2010. Podcast: 17 min. Available from: http://podcasts.aaas.org/science_transl_med/ScienceTranslMed_100707.mp3

[3] Broder S. Twenty-Five Years of Translational Medicine in Antiretroviral Therapy: Promises to Keep. Sci Trans Med. 2010;2(39):39ps33. DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000749 Accompanied by: Podcast transcript. Available from: http://stm.sciencemag.org/content/suppl/2010/07/05/2.39.39pc5.DC1/ScienceTranslMed_100707.pdf

Erratum

The authorship was originally attributed to Samuel Broder (Celera, Alameda, CA, USA) and Annalisa VanHook (American Association for the Advancement of Science, Washington D.C., USA).